A recent controversy surrounding the biography of Yuri Gagarin, and involving NPR, highlights the gaping divide separating academic history writing and the public presentation of history. Last week Robert Krulwich, who writes on science for NPR, posted a blog based on a 1998 book entitled Starman (http://www.npr.org/blogs/krulwich/2011/03/21/134597833/cosmonaut-crashed-into-earth-crying-in-rage). The blog uncritically presented the book’s dubious account of the tragic death of the cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov on April 24, 1967. Gagarin was the back up for that flight. Historians at NASA immediately alerted fellow blogger Asif Siddiqi and me to the blog. Asif, who knows the history of Soviet space better than anyone, posted his critique of the NPR article, followed by many others (see the comments following the blog above). To his credit, the journalist involved has decided to investigate further(http://www.npr.org/blogs/krulwich/2011/03/22/134735091/questions-questions-questions-more-on-a-cosmonauts-mysterious-death?sc=emaf).

Category: Soviet Era 1917-1991

For my first post for the blog, I decided to draw from a forthcoming project of mine on the history of Soviet science and technology as it intersected through the apparatus of repression. What follows is a short summation of several chapters on the so-called sharaskha system. I was led to this topic partly by an interest in censorship during the late Soviet period. As many older Russians undoubtedly remember, by the early 1970s, the culture of underground or samizdat literature in the Soviet Union had evolved into a highly risky but established system for disseminating information among the dissident community. Banned literature—poems, fiction, accounts of current events—vied for space in poor quality publications circulated through a clandestine network. One such type-written manuscript of less than two hundred pages struck a chord among many samizdat readers despite its unusual subject matter—it described the work of an aircraft design organization from three decades before. Known by the title, Tupolevskaia sharaga, the manuscript attracted a large leadership and became a classic in the literature of dissent.

In vivid language, its anonymous author recalled his experiences as an engineer in a special prison workshop headed by the giant of Soviet aviation Andrei Tupolev.

The prison camp had been organized sometime in the late 1930s and housed hundreds of leading Soviet aviation designers who, cut off from the outside world, labored through physical and psychological hardships to produce new airplanes for the cause of Soviet aviation. By coincidence, Tupolev died soon after this manuscript began circulating. In Moscow, he was given a state funeral and his contributions eulogized by Leonid Brezhnev, but unsurprisingly there was no mention of his arrest, incarceration, and work in a labor camp during the Stalin era. The anonymously authored memoir, smuggled out to the West and published in English, remained a peculiar anomaly in the historical record, suggesting tantalizing lacunae in Tupolev’s official biography. [1. A. Sharagin, Tupolevskaia sharaga (Frankfurt: Possev-Verlag, 1971). A French translation was also published in 1973.]

Colleagues at cocktail parties and in the lounges of hotels after conferences have often asked me why Yuri Gagarin was chosen to be the first cosmonaut on April 12, 1961. This blog, excerpted from a draft of my book on Gagarin, describes the circumstances that led to Gagarin’s selection as the world’s first spaceman.

Warriors into Spacemen

The decision to send a man into space begged a number of questions, including the type of person required for the job.[1] Sergei Korolev, the Soviet rocket pioneer known publicly as the “Chief Builder” until his death in 1966, had initially argued that the first cosmonaut should be an engineer – perhaps even himself – although he soon backed away from that position. The debate was quickly decided in favor of a fighter pilot, although the space capsule was totally automated and required little “piloting.” The decision had more to do with politics and conceptions of heroism than anything else. It was assumed that fighter pilots had the courage to overcome the potentially terrifying experience of weightlessness and that they would follow commands no matter how dangerous the mission. Besides, if something glorious in the air was to be done – should the cosmonaut survive — then it seemed obvious to most that it should be a fighter pilot, the most heroic of the heroes in the Soviet pantheon after World War II. Finally, drawing the first cosmonaut from military ranks was essential to Korolev’s ongoing campaign to win over the military leaders, who would never have tolerated a mere civilian as the first human being in space.[2]

In the autumn I attended a conference on “Unthinking the Imaginary War: Intellectual Reflections of the Nuclear Age, 1945-1990” in London. The very same weekend another cohort of academics were attending a conference on “Accidental Armageddons: The Nuclear Crisis and the Culture of the Second Cold War, 1975-1989” in Washington. The Cold War is a hot topic at the moment. Increasingly scholars are taking interdisciplinary approaches, using film, novels, and art, to explore how this ever-looming, but unconsummated, conflict was imagined, and the emotions it generated. In London I learned how peace activists, scientists, politicians, and the general public reacted to the nuclear threat, with papers on a range of countries including Germany, Britain, France, Japan, and the USA. Curiously, the Soviet Union, the red menace behind so many of these anxious projections, often seems to be missing. The question of how Soviet society regarded its adversaries in the capitalist world, and how fears of nuclear annihilation were handled, is nevertheless a fascinating one and some interesting work is beginning to appear.

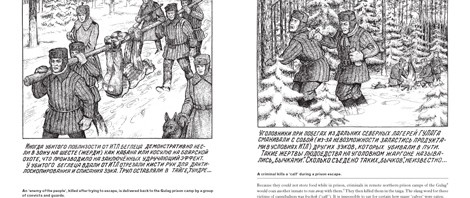

From time to time, I want to share some of the remarkable photographs, paintings, drawings, artifacts and documents available to the public in the Gulag: Many Days, Many Lives archive. Here we see one of my favorite images–one I write about briefly in my forthcoming book, Death and Redemption: The Gulag and the Shaping of Soviet Society, and that I use as a key illustration in virtually every public lecture I give on the subject.

The main sign reads “Graves of the Lazy” (Могила Филонов – with the latter term a Gulag acronym for the “False Invalids of the Camps of Special Designation”). The burial markers in this “propaganda graveyard” read names and percentages like “Gaziev – 30%” or “Mavlanov – 22%.” The meaning would have been quite clear to prisoners. As a fellow prisoner and brigade leader told Janusz Bardach, “You work, you eat. You stop working, you die. I take care of my people if they produce, but loafers don’t stand a chance.”[1. Janusz Bardach and Kathleen Gleeson, Man Is Wolf to Man: Surviving the Gulag (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), p. 204]

This coming April 12 marks the 50th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin’s historic flight into space. In honor of that jubilee, and also because I’m finishing a biography on the world’s first cosmonaut, I’ll be blogging on and off about various aspects of Gagarin’s life and legend.

More than just a delivery vehicle, Gagarin’s ship, the “Vostok,” was a special kind of space portal: it connected the super-secret world of national defense to the Soviet public realm. In passing through that portal, Gagarin had done something totally unprecedented — as shocking, perhaps, as the actual technical feat of the flight. He had revealed his secret identity and life. This act of revelation, in a system that constructed elaborate barriers to protect closed worlds from public view, created an initial sense of panic as well as joy among Gagarin’s handlers and commanders, many of whom worked in the ranks of the KGB. They were overjoyed that he had survived his ordeal, his trial by technological terror. They were eager to trumpet the flight as proof for the whole world to see that the Soviet Union had a superior way of organizing its political and technological affairs. They wanted to brag. But they were terrified that in the process of talking about themselves they might compromise national security. One eyewitness account remembered the alarm of KGB officers who arrived at the landing site of Gagarin’s charred capsule, which alit about 2 kilometers away from Gagarin. People were climbing all over it, snapping pictures (photography of military objects was strictly forbidden!), and stripping off pieces as personal souvenirs. One souvenir seeker managed to “privatize,” in his words, a few tubes of space food. Within hours, before a security cordon could be reestablished and a black tarp placed over the capsule, the details of a top-secret enterprise had been dangerously exposed to the public.[1]

Just before Christmas I saw the newly released The Way Back, in many ways a typical escape story. Directed by Peter Weir, the film tells the incredible story of how a young Polish officer, arrested in 1939 and sent to the Siberian Gulag, plots his escape – and with a small band of fellow inmates – manages not only to make it out of the camp, but also through Mongolia, the Gobi Desert, and the Himalayas to India. Along the way they face many of the knotty moral issues characteristic of the genre: Should they wait for weakened members of the group? When must they rest, and when battle on? And can they risk letting a newcomer – in this case, a young girl Polish also on the run – join them? There are some nice touches: I particularly like the way the girl acts as a go-between, passing on information about the men which they are too buttoned-up to share amongst themselves.