In the early years of the Russian American Company, there was an odd incident that led to establishment of three “Russian” forts on the island of Kauai. The reasons for that are somewhat complicated (and the study of several interesting books [1. Most recently, Peter R. Mills, Hawai’i’s Russian Adventure: A New Look at Old History, (Honolulu, 2002)]), but the physical evidence of the venture is the Hawaiian state park at the site of the “Russian” Fort Elizabeth. When I first arrived at the site as a tourist, my first thought was that this was not “Russian” at all.

It’s easy to explain my reaction through a set of pictures. “Russian” colonial forts were regularly constructed of wooden palisades and packed earth – rarely if ever stone, which was a practical supply decision in Russia, where wood was common and stone was not. The forts were mostly rectilinear, with watchtowers in the corner. Look, for example, at this map of the fort in Tobol’sk from the beginning of the eighteenth century, or at the walls of distant Kamenogorsk from later that century. The stone structure in both images is the church, not the walls.

This style of fort building followed through the eighteenth centuries expansion to Kamchatka, and then the Aleutian Islands, Alaska, and then on to Fort Ross in California in the early nineteenth century. “Russia’s” colonial forts remained wooden palisades with watchtowers.

Therefore, Russians building a Russian fortress on Kauai out of stone would have been atypical, since the other outposts of the Russian American Company were all built in “traditional” style, in wood. It’s arguable (and has been discussed in the literature), that the local Hawaiian labor force who constructed the fort were used to volcanic stone, making the material a viable alternative. I personally find that to be a reasonable conclusion, though Kauai was heavily forested at the time, so certainly wood was also available and the Company had been using indigenous labor in America to build “traditional” wooden forts elsewhere.

However, the bigger surprise is the style of the fortress, which is built along the lines of a so-called trace italienne fortress – in a pointed star pattern to provide maximum advantage for its cannons. I do know that there were some trace italienne fortresses in the European part of the Empire (Smolensk being probably the best known), but it had not been used as a style of fortress throughout Siberia or America previously to this moment. In other words, how “Russian” is Kauai’s fort?

Understanding the fort begins with the role of Georg Anton Schaeffer, a German in the Company’s employ. When he arrived in Kauai in 1815 on a recovery mission for the Company, he took advantage of Kauai’s precarious position in the island chain to negotiate with its king, Kaumualii, a favorable agreement with Russia and the Company. After that, Schaeffer supervised the constructions of the forts on Kauai, the largest of which was Fort Elizabeth, with its strategic position on Kauai’s southern coast. Despite Schaeffer’s ambitions, when news of the project reached the American office of the Company on Sitka, he was recalled and the deal was abandoned. With both British and American interests in Hawai‘i, much less the strength of Kamehameha and the weak position of Kaumualii, the Company could not afford a Hawaiian blunder like Schaeffer’s attempted annexation.

Looking at the fort today, its trace italienne features strongly suggest a European continental background, not a Russian colonial structure. Schaeffer, a German doctor, likely relied upon the fortification designs he was most familiar with at home, which would not include Russian outposts in Siberia, though presumably he has seen those in Russian America. As a result, I find it hard to consider Fort Elizabeth a “Russian Fort” (as it’s still identified on Kauai). Maybe a “Russian American Company Fort” would be a better compromise, but why not Schaeffer’s fort?

While the fort on Kauai might be a small incident in the history of the Company (or an even smaller one in the history of the Russian Empire), it does raise some significant questions about the way in which we conceptualize Russian history and the history of empires in general. One lesson is that imperial expansion in the Pacific (if not Siberia) was frequently at the mercy of largely independent agents. Though I find this to be a bit obvious, it’s an idea too often missing from work on Russia in the Pacific. A second lesson is that opportunities may exist, but timing is everything. The Company had success around the Pacific Rim during the Napoleonic Era, such as the establishment of Fort Ross in California, but attempting a colonial foothold on Kauai after the British returned to the Pacific was a proposition that would take an enormous investment and antagonize a rival with a much greater call on local resources, and therefore the probability of success was tiny. A third point is that in the history of colonial ventures, certainly small acts can have big consequences, but for every big success arising from a highly conditional act by a small actor, there are a large number of inconsequential and unremembered (but still historically important) failures. Considering failed colonial ventures might be as profitable as considering Russian “successes.”

I hope to spend more time in the upcoming year raising issues about Russia’s imperial past, and the way it is remembered in the modern day.

6 replies on “How “Russian” is Kauai’s Fort Elizabeth?”

Hi Matt, I enjoyed your post. I’m an outsider to both Tsarist-era history and the historiography on Russian expansion into Siberia and beyond, but I’d like to raise a related question: to what extent should we understand the Russian-America Company, particularly in California and Hawaii, as an explicitly imperial, rather than commercial venture?

For instance, if the Russians at Fort Ross, who were never more than a several dozen in number, presented themselves as imperial agents, why were they not evicted by the Spanish, who had a sizable presence in both San Francisco and Sonoma (where the California Republic was declared in 1846). Why did the Russians settle fifteen miles north of the mouth of the Russian River, where there was no protected anchorage? Bodega Bay, a natural harbor formed by the San Andreas fault, is 20 miles to the south. To me, this suggests the Russians always understood themselves as trespassers, and tried to be as unobtrusive as possible. It’s also interesting that when the Russians abandoned Fort Ross in 1841, they cited declining revenues from seal hunting and the failure to develop profitable agriculture in the narrow strip they occupied between the ocean and the coastal range. (Paradoxically, some of the most coveted Pinot Noirs in Sonoma County are grown today in the same vicinity.) And, of course, the Russians sold Fort Ross to another entrepreneur, John Sutter.

This leads me to my big point: perhaps the appropriate parallel for Fort Ross and Fort Elizabeth can be found not in earlier Russian ventures in Siberia, but in Fordlandia, Henry Ford’s rubber plantation in the Brazilian Amazon. It’s unusual, obviously, to think of the Russian presence in the new world in this manner. But why should we not? Perhaps Fort Ross and Elizabeth, peripheral at best to the story of Russian imperialism, provide an opportunity to rethink many of our broadest assumptions about Russia in the 19th century.

Hi Steve, I appreciate the idea that we need to broaden our comparative perspective to understand Russia’s various ventures. I definitely agree there’s a lot more that could be done than we have so far, but I also don’t want to separate “colonial” efforts from “commercial” ones. I do think there are tremendous opportunities to situate “Russia’s” ventures among the other colonial “factories” across Asia and the Pacific. In his recent book, Ilya Vinkovetsky makes a strong argument that the establishment of the Company marks a break with Russia’s colonial past as the Company (and the circumnavigation voyages) demonstrated Russia’s interest in paralleling colonial and scientific ventures of other European Empires. However, I don’t know that I would be comfortable with the Fordlandia comparison. The idea of contrasting an early nineteenth century colonial enterprise with a twentieth century project still strikes me as a bit unwieldy, though I’d enjoy hearing more of your ideas why it might work.

What I had in mind with the Fordlandia comparison is re-casting the Russian presence in North America and Hawaii as an explicitly (and aggressively?) commercial form of imperial venture overseen by a non-state actor. It’s not often that we think about Russia in these terms.

I have to run off to class in a few minutes, so I’ll end quickly with a shameless plug for Fort Ross. 2012 is the 200th anniversary of the founding of the fort. Anyone interested in the fort’s bicentennial activities, can click on the following: http://www.fortrossinterpretive.org/bicentennial-2012/

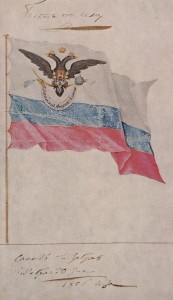

Hi Matt – I wonder what year the illustration of Petroplavosk- Kamchatka outpost in your article about Port Elizabeth was done and by whom? Thanks – Sally

[…] A very interesting ‘take’ on the history of the fort is available on the Russian History Blog HERE. […]

[…] typical Russian fortress would be built of wood and had a rectangular shape with watchtowers in each corner of a wooden […]