I initially planned this post to focus on the lands around Gatchina proper where the cheese master lived and worked. But then I started following up on a couple of comments made about the last post, and suddenly I’d written 1000 words. So, instead of the lands around Gatchina, here are more thoughts about trade routes, the French Revolution, bull-running (!!) and being an old Russia hand.

After I posted about the last entry in this tale on Facebook, I got a couple of comments that I felt like I had to investigate. Did I really think, Alexander Martin asked, that the cheese master had traveled to Russia along that long overland route I mapped out, or would he have been more likely to travel up the Rhine, and then enter Russia by sea? It’s a good question, and one that I certainly can’t answer for certain. I suspect, though, that the overland route is indeed the one that Tinguely traveled, for several reasons.

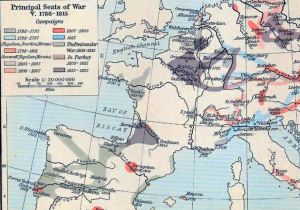

The first reason has to do with the status of Rhine shipping at the time. Tinguely’s travels happened just before a series of major reforms made Rhine commerce more feasible for more people. According to Robert Mark Spaulding, in 1789 travelers along the Rhine would have been met with “dilapidated infrastructure, physical impediments, tolls, city monopolies, and the privileges of the boatmen’s corporations.” Something like 30 or 32 separate toll stations stopped river traffic between Strasbourg and the Dutch border alone—and their tolls were unpredictable and subject to “negotiation” between shipping agents and toll collectors. Only when revolutionary France began to extend its authority did the situation begin to change. Initially, more unified French control made river transport more stable; even after Napoleon’s fall, an international commission was established to ensure that the river remain an important part of the European system of trade. But at the time of Tinguely’s travels, the Rhine might have been a faster option, but it was not necessarily a better one than the long overland route.

(As a side note to this, the French Revolution may also have affected this story in another way. In 1790, Tinguely was trading regionally. By April 1, 1792, he had made it to Russia, and was working for the Gatchina palace administration. If he’d actually gone to Russia early in that period, perhaps the Rhine option was a real choice, whatever the issues of tolls and the like. But if he headed to Russia in late 1791 or early 1792, the winds of war were certainly already blowing in ways that suggested the Rhine was about to be not a very safe place. War did not officially break out between revolutionary France and its pro-monarchy neighbors until later in April, 1792, but Austria and Prussia had made a declaration against the revolution already in late 1791. Travel through those regions at that time may well have seemed like a particularly bad idea.)

A second reason has to do with the cattle trade more generally. Again in response to that last blog post, Jonathan Bone found another possible source of information, the remarkably titled 1805 publication European Commerce, Shewing New and Secure Channels of Trade with the Continent of Europe: Detailing the Produce, Manufactures, and Commerce, of Russia, Prussia, Sweden, Denmark, and Germany; as Well as the Trade of the Rivers Elbe, Weser, and Ems; with a General View of the Trade, Navigation, Produce, and Manufactures, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland; and its Unexplored and Improvable Resources and Interior Wealth. Illustrated with a Canal and River Map of Europe, by J. Jepson Oddy (“member of the Russia and Turkey or Levant Companies”) (sadly for our purposes, the only map that made it into the Google Books version is of Spain). Again, the timing of the book is significant. It talks of the need for Britain to change its trade routes in response to recent events—again, the French Revolution, and particularly the rise of Napoleon—and to seek greater trade with places further north and east. In essence, it is a response to uncertainty in European markets. Indeed, the volume includes the text of several specific recent trade agreements between Great Britain and Russia that had tried to smooth over relations that had gone badly during Paul’s reign.

Oddy’s book particularly notes that one of the major exports from Russia during this period were cattle and their products. Mostly, it has to be said, their products. Tallow became a huge export—from 900 tons exported to Britain over the entire period from 1752 to 1766, up to 27,450 tons in 1803 alone. According to Oddy, the entire tallow exports from Russia in that year were worth nearly £2,000,000. This huge sum was indicative of the large scale of cattle production in Russia: “if the breeding of cattle cannot be reckoned the first, it certainly is the second consideration of importance to the Russian empire, from the tallow, hides, salted beef, glue, and even the very bones which are exported.” Not only were these products exported, but live cattle were, as well: “In such abundance, and so cheap are the cattle in the Ukraine, that large quantities are exported to Silesia and other places, and annually driven to Mosco, Petersburg, Revel, and Riga.” (89) Those cattle routes would not have been exactly those traversed by Tinguely, but they do suggest that overland routes for cattle were used in the region more generally.

Given that I’ve ended up falling into this particular post, I may as well follow one last odd little corner of the story that bizarrely returns to trade and cattle (though not the cattle trade). Not too long after his book was published, Joshua Jepson Oddy entered politics in Britain, standing for a seat in Parliament as a newcomer to the town of Stamford. He ran as “a Russian merchant of some consequence” (though he was actually a bankrupt) and on, of all things, a pro-bull-running platform. Oddy failed—and when he stood again one of his opponents actively campaigned against Oddy’s support of bull-running. (In the end, bull-running was not the source of the end of Oddy’s campaign—his financial schemes and apparent untrustworthyness were.)

I’ll admit, I’m fascinated by this side route from the main story I’m telling. Is this the first case of an Old Russia Hand trying to parlay his expertise into politics? Probably not, but it’s sort of an amazing one.

(On Rhine river trade, see Robert Mark Spaulding, “Revolutionary France and the Transformation of the Rhine,” Central European History 44 (2011): 203-226, esp. 209; and Hein A. M. Klemann, “The Central Commission for the Navigation on the Rhine, 1815-1914,” ECHR working paper; for Oddy’s book, see here; on Oddy and bull-baiting, see Narrative of the Proceedings at the Stamford Election, February 1809 (Stamford, 1809) and R. G. Thorne, “Stamford,” at http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/constituencies/

3 replies on “The Case of the Dead Cheese Master, Part V: Twists and turns”

Your link to the Oddy book is borked, but a better source for it is Archive.org, where you can presumably see all the maps (I didn’t know which pages they were on, so didn’t check): https://archive.org/details/europeancommerce02play

Thanks for noticing the borked link–I’ve fixed it now (and thanks for the other link, though it, too, seems to be mapless, alas).

[…] Smith follows the case of the dead cheese master down a sidestreet to commerce on the Rhine shortly after the French […]