This year while I’m on a research fellowship, I’m helping the University of Utah’s Asia Center to organize an interdisciplinary conference. We’re planning it around the theme of “Asia in the Russian Imagination,” but are expecting it to be more broadly concerned with the history of Siberia, Central Asia, and the Russian Far East and North Pacific. The conference will be held at the University of Utah’s campus in Salt Lake City on March 23-24, 2018. Over the past three years, the Asia Center’s “Siberian Initiative” has sponsored talks on anthropology, environmental studies, history, film studies, and linguistics, and we are continuing this interdisciplinary approach to Russia in Asia/Asia in Russia at our conference.

Category: Transnational History

The more time I’ve spent thinking about the Chuck Steinwedel’s excellent Threads of Empire, the more I’m taken by the idea of imperial threads. The intertwined purpose of policy is difficult for anyone to unwind. I think this is an important contribution just for the reminder about the multivalent nature of imperial governing strategies.

In the excellent chapter on the middle of the eighteenth century (“Absolutism and Empire”), Steinwedel begins with the Ivan Kirilov and Kutlu-Mukhammad Tevkelev’s expedition that led to the establishment of the new fort of Orenburg. The expedition departed Ufa in April 1735, and immediately ran into difficulties in the form of an uprising, which eventually would be known as the Bashkir War of 1735-40. This is the point when I start to think about threads of empire. Steinwedel thoughtfully analyzes the outcome of the revolt upon the local populations, and thinks about the ways in which local identities were shaped by these experiences and the changing relationship to state authorities. Towards the end of the 1750s, Tevkelev produces an examination of state policies toward the Kazakhs, which considers whether the nomads could be encouraged to settle or would continue to follow their traditional lifestyle. Summarizing the report, Steinwedel assesses its evaluation: the “Kazakhs had already fallen in love with trade” (p. 65).

Although my academic work gives no hint of this, I’ve always been oddly fascinated by the interwar period. I know exactly where the fascination came from: mystery novels. No, even more specifically, British mystery novels, where the specter of war is rarely foregrounded but often there, from poor (well, not poor) shell-shocked Lord Peter Wimsey to clever and displaced Hercule Poirot. I even love more recent mystery novels that take interwar Britain as their setting—an awfully popular setting, really, perhaps because everyone is trying to recapture the allure of Sayers and Christie.

Because I’m me, there is one extra thing I always notice in these novels—the random Russian émigrés who show up around the edges of the stories, making their lives in the wider European world. In Dorothy L. Sayers’ Have His Carcase the murder victim is a young Russian émigré working as a professional dancer at a resort hotel. In her Strong Poison Lord Peter visits the smoky rooms of hipster Bloomsbury, where Russians fry sausages and play atonal music.

Yesterday I got a book out from the library that made me think about those Russians wandering about interwar Europe. On the surface, there’s no reason for the book to lead me there—it’s a history of the colonization of Siberia, by V. I. Shunkov, from 1946. But the book had this stamp:

It says Библиотека русских шофферов, or the library of Russian chauffeurs, and gives an address in Paris. Well, of course I had to find out a little bit more about that.

The British expat community found living in Russia to be a great hardship, regularly complaining about the inhospitable weather and its remote location. Even worse, Russia was expensive, especially for prominent foreigners who expected access to some of the finer things. The British envoy to Russia at the beginning of the eighteenth century (Charles Whitworth ) was one of those men. Fortunately, we happen to have access to a couple of his shopping lists (for 1705 and 1706) that provide some insights into the sorts of luxuries a diplomat needed to maintain his position in society. These items were also treated a special project for his staff to acquire, suggesting they weren’t always available in the local markets.

All the items below are on his list from July 1705. In Moscow, Whitworth instructed the British consul to purchase:

6 hogshead of good claret (1 hogshead is about 300 liters)

1 hogshead of good French white wine

1 hogshead of Languedoc or any other good wine

1 or 2 chests of Florence if they are to be procured

1 barrel of English ale

2 dozen drinking glasses

10 dozen of lemons

5 dozen China oranges

A quantity of Dry Sweatmeats

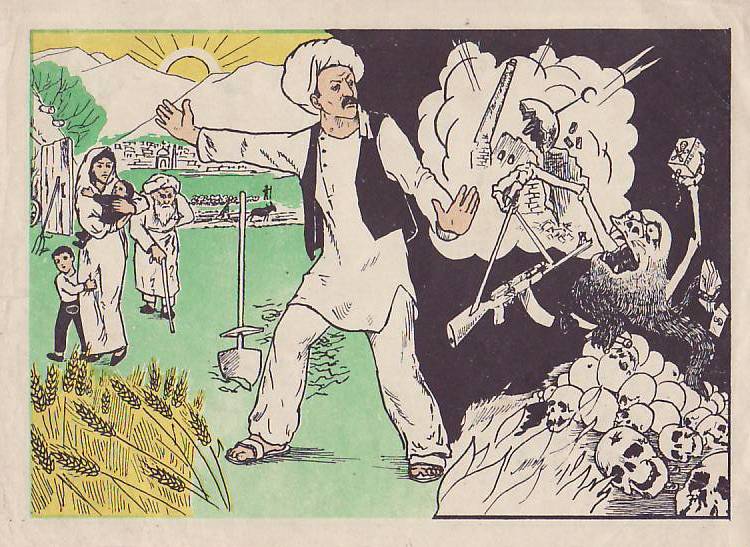

Nineteen seventy nine was a pivotal year in twentieth-century history – as momentous, perhaps, as 1945 and the defeat of the Axis powers in World War II. The Soviets invaded Afghanistan; Iranian revolutionaries seized American hostages in Tehran and overthrew the Shah; Islamic fundamentalists attempted to seize Mecca; and enraged crowds of Pakistanis, goaded on by Islamic extremists, attacked the US embassy in Pakistan. With the benefit of hindsight it is clear that these events signaled a radical break from the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. The world had changed, and a new kind of war had emerged; yet the United States and the Soviet Union continued to fight proxy wars against each other, blinded by their own ideological obsessions and incapable of discerning the new common enemy of Islamic fundamentalism.

Nineteen seventy nine was a pivotal year in twentieth-century history – as momentous, perhaps, as 1945 and the defeat of the Axis powers in World War II. The Soviets invaded Afghanistan; Iranian revolutionaries seized American hostages in Tehran and overthrew the Shah; Islamic fundamentalists attempted to seize Mecca; and enraged crowds of Pakistanis, goaded on by Islamic extremists, attacked the US embassy in Pakistan. With the benefit of hindsight it is clear that these events signaled a radical break from the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. The world had changed, and a new kind of war had emerged; yet the United States and the Soviet Union continued to fight proxy wars against each other, blinded by their own ideological obsessions and incapable of discerning the new common enemy of Islamic fundamentalism.

A captivating and timely film tells the story of the ten-year Soviet war against Afghanistan (Afghanistan 1979: The War that Changed the World: http://icarusfilms.com/new2015/afg.html). The war triggered an ever-increasing cycle of violence. Fueled by American and Soviet weaponry – which armed future enemies of both the United States and Russia – Afghanistan became a failed state, creating a power vacuum filled by terrorist movements of various sorts and spreading like a cancer throughout the region. Over a decade more than one million Afghanis died – mostly civilians – and millions more became refugees. At least 15,000 Soviet soldiers fell in battle, and the aura of the Red Army’s invincibility, which had been so crucial to Soviet power and prestige around the world, was shattered.

Curiously, despite its enduring and tragic significance, few historians or political scientists have studied the war in depth: the reasons for the Soviet invasion, the conduct of the war, the relationship of the failed war to the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union, and the role of the war in creating the world in which we now live. The primary piece of documentary evidence for the decision to invade comes from a single hand-written page from the Soviet Politburo leadership. The document does not even mention Afghanistan, referring to it as simply country “A,” and it provides little insight into the Soviet decision to send in troops. It is as if Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet leader at the time, was a kind of Mafia Don, and his fellow Politburo members and generals his mob family bosses. Through various winks and nods – but with nothing concrete or coherent presented as an explanation – Brezhnev let it be known that it was time to do a “hit” on the increasingly annoying and irksome Soviet clients. By comparison there has been far more research and analysis of the war with which the Soviet invasion is often compared –the American Vietnam War – though arguably the Afghan war has had a much greater impact on the course of world history.

Whatever the exact reasons for the invasion, Afghanistan was certainly considered a strategic prize, both for the Soviet Union and earlier for the Russian Empire, when the region became a pawn in the “Great Game” for control between the British and Russian Empires. The Soviets were the first to recognize the new state of Afghanistan in 1919. Relations remained close, as the Soviets attempted to use Afghanistan as a buffer zone between itself and Pakistan and Iran. Only an attempt at radical communist revolution – generated not by the Soviets but independently by more extremist communists within Afghanistan in April 1978 – destabilized the situation. The revolutionaries’ agenda of social, agrarian and economic reform immediately created stiff resistance and polarized the country, radicalizing the political environment and opening the way to more extreme forms of political expression from all sides. Afghani communist officials persecuted religious leaders, causing blowback that drew inspiration from the Iranian Revolution in February 1979 and the Ayatollah Khomeni. As resistance to the new communist Afghani President Nur Mohammad Taraki grew, so too did Afghani appeals for Soviet aid. Meanwhile, the country continued to splinter, as warlords and tribal leaders began to fill the vacuum of power created, unintentionally, by the revolutionary upsurge.

One of the more intriguing claims in the documentary is that Brezhnev’s advancing dementia and lack of stamina played a central role in the invasion. Manipulated by alarmist memoranda from the KGB head Yuri Andropov, and their suggestion that immediate action needed to be taken, Brezhnev assented to intervention – though just what kind and why was unclear, and perhaps will never be known if in fact Brezhnev was not entirely lucid, as seems to have been the case. The seeming success of the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, which Andropov believed produced a more docile and controllable client state to its west, perhaps fed the delusional notion in the Kremlin leadership that Afghanistan, the graveyard of empires, could be just as easily invaded, and with just as few military and political consequences. Eurocentric views of the Afghanis as inferior, similar to US views of the Viet Cong, also seemed to have made the Soviets underestimate their foe.

There are many compelling stories and revelations in the film. The Soviets, for example, early on trained Soviet Central Asians to form a special battalion that would wear Afghan uniforms – so that Soviet military intervention could be disguised in May 1979, before the actual invasion in December of that year. The CIA countered, on the borders of Pakistan, with support for anti-communist insurgents. A state of civil war, with various war lords in control of the provinces, emerged by December 1979, when another fateful event occurred. President Taraki’s erstwhile ally and Prime Minister Hafizullah Amin overthrew his revolutionary comrade, commanding his secret police to strangle him.

The documentary claims, though it is not clear based on what evidence, that the Soviets believed Amin was an American pawn. In his brief time in power Amin waged a campaign of terror and purges against the dead former President’s real and suspected allies. At one point the Soviet officials in Kabul charged with protecting Amin from a counter-revolution were now ordered by the Soviet secret police to assassinate him and his entourage. They tried to poison the President’s drink at a dinner in the palace – by slipping poison into his Coca Cola, with which the Soviet agents were not yet familiar. Coke, however, was not “it.” It apparently neutralized the poison and the dining party survived! So the Soviets instead bombed the presidential palace to smithereens, sure that they would find evidence that Amin was a CIA pawn (just as, perhaps, the US was sure in its invasion of Iraq that Saddam Hussein was developing weapons of mass destruction). There was no such evidence; Amin was simply a loose cannon — and not even a Chinese spy, as other KGB agents thought might be the case.

By the mid-1980s it had become clear to Mikhail Gorbachev that the war was a strategic, political, and military disaster. The architect of Perestroika and new political thinking makes a fascinating and typically self-serving appearance in the film. As a young Politburo member, he claims that most of the political leadership was excluded from the initial decision to invade, and that the invasion was a kind of coup orchestrated by Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrei Gromyko, General Dmitrii Ustinov, and Brezhnev. Of course, this position perhaps too conveniently absolves Gorbachev of complicity in the invasion on December 28, 1979. The absence of documented records makes it impossible to say. When Gorbachev in the film proclaims fatefully, “you can’t rewrite history,” it is entirely possible that he is the one doing the rewriting.

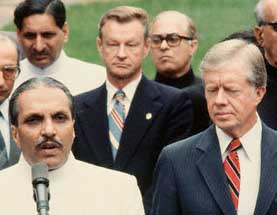

Among other things, the Afghan war derailed the politics of Détente, which Jimmy Carter and his hawkish National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski decisively ended. Providing lethal aid to the Mujahideen, they intended to make Afghanistan the Soviet Union’s Vietnam, payback for the American nightmare that had only ended five years previously. A boycott of the Moscow Olympics soon followed, as well as termination of broad-ranging intellectual and cultural exchanges — as well as collaboration in space exploration — between the United States and the Soviet Union, all initiated by Nixon and Kissinger.

Especially blameworthy in this story, as recounted in the documentary, is the role of the ideological Cold Warriors of the Reagan Administration, who were determined to defeat the Soviet Union at all costs, even as Gorbachev attempted to rely on the most moderate forces in Afghanistan, in order to achieve a national reconciliation and remove Soviet troops. Reagan’s advisors, gleeful at the humiliations suffered by their ideological foe, armed the most radical Jihadists they could find with billions of dollars of sophisticated weaponry and training, thus creating a kind of hothouse for growing future terrorism. Stinger missiles — handheld anti-aircraft weapons — were given to the Mujahideen, taking down hundreds of Soviet attack helicopters. Sly Stallone exploited the triumphal embrace of the Islamic Jihadists in 1988, producing Rambo III, in which Rambo heads a CIA operation to help Mujahideen blow away Soviet soldiers. Reagan greeted Mujahideen in the White House as partners in defense of religious faith and freedom against Godless commies.

If Brezhnev’s dotage played a role in the initial Soviet invasion, goaded on by hawks within the Soviet military industrial complex, Reagan’s own advancing senility in the mid-1980s allowed Cold Warriors like Richard Pearle, blind to the dangerous implications of their Afghanistan gambit, to enact a fatally-flawed policy in the Middle East.

This is a well told story that clearly outlines the series of blunders and missteps that led to the overthrow of Amin, the invasion, the installation of the new Soviet-chosen leader Babrak Karmal and to the many unintended and tragic consequences that resulted – especially for the United States and the Soviet Union, who armed their current and future enemies in waging a proxy war against each other. It contains excellent archival footage as well interviews with important historical figures on all sides of the conflict at the time. This documentary, in short, is a must see for anyone interested in the blunders and miscalculations of both Soviet and American leaders that produced the terror-infested world in which we now live.

History is being blithely tossed about these days by everyone from Vladimir Putin himself to Sarah Palin and John McCain. What is the real story? Is there a real story?

To answer that question, I invited two eminent historians – well, one historian and one historically minded political scientist, Serhii Plokhii and Mark Kramer, both of Harvard, to speak at MIT on this exact situation. They spoke on Monday (3/17), the day after the Crimean Referendum and the day before the Russian President’s speech.

In balmy Culver City near Los Angeles, not far from the campus where I teach, there is a wonderful little museum called the Museum of Jurassic Technology (http://mjt.org/). The museum contains a Russian tea room and aviary on the roof. Next to the Russian tea room are two exhibition halls. One contains portraits of all the Soviet space dogs. Another is devoted to the life and myth of Konstantin Tsiolkovskii, whose translated technical works as well as science fiction are available in the museum gift shop. I often thought about that exhibit –and how odd it must be for casual visitors — as I worked about 40 miles to the south, in the place where Richard Nixon grew up, at the Nixon library and archives.