This year while I’m on a research fellowship, I’m helping the University of Utah’s Asia Center to organize an interdisciplinary conference. We’re planning it around the theme of “Asia in the Russian Imagination,” but are expecting it to be more broadly concerned with the history of Siberia, Central Asia, and the Russian Far East and North Pacific. The conference will be held at the University of Utah’s campus in Salt Lake City on March 23-24, 2018. Over the past three years, the Asia Center’s “Siberian Initiative” has sponsored talks on anthropology, environmental studies, history, film studies, and linguistics, and we are continuing this interdisciplinary approach to Russia in Asia/Asia in Russia at our conference.

Category: Russia in World History

I am among those who eagerly awaited the publication of Erika Monahan’s book, The Merchants of Siberia. For a number of years I’ve been developing a study of what one might call (if one were inclined to use flamboyant catch phrases to draw popular attention to scholarly subjects) The Early Modern Silk Road. This is essentially a study of Central Eurasia’s position at the heart of overland networks of exchange during a period when most have assumed that they had diminished to the point of insignificance, and few have thought to look and see if that assumption was correct. The Merchants of Siberia advances a related argument and marshals a substantial amount of original evidence to support it. Erika Monahan was kind enough to provide me with working drafts of select chapters as her project was coming to a close. But it was only when I had the published book in my hand that I was able to appreciate the magnitude of her achievement.

Merchants of Siberia complicates and enlivens our evolving picture of commerce and trade in early modern Russia. Noting the links between Russia’s growing involvement with European trading partners and trading activities on Muscovy’s southern and eastern frontiers, Erika Monahan calls for a closer focus on the role of the Russian state and Eurasian merchants as facilitators of east-west and north-south trade. As part of this move, she emphasizes that, from the point of view of both merchants and agents of the Muscovite state, Siberia was far more than just a store of natural resources, highlighting in particular its place as “a node in important trans-Eurasian routes.” This is a productive avenue of exploration. Erika’s work examines western Siberia’s under-appreciated early modern connections with Central Asia. Muscovy was indeed connected to diverse states along its multiple frontiers. Reading about these interactions, but coming at these same issues from the point of view of a historian of the nineteenth century, made me wonder, what standard do we have for calling a particular trade vibrant and a particular route or set of routes important?

Importance seems to be a relative concept. Continental trade to and through Siberia was important – undoubtedly so, I would argue, to the communities that resided there. As for transit trade, it was surely important as well, but the difficulty – not to mention the sheer length – of the routes made long-distance transport daunting and time-consuming under the best circumstances, and of course expensive. The routes between Siberia and east and central Asia all came with a set of challenges and risks. Climatic conditions compelled trade in Siberia to follow a seasonal rhythm – making passage of goods impossible for months at a time. The fact that these trade routes nonetheless persisted seems to point to both the dearth of alternatives and the reality that there were parties who had a vested interest in these routes, whatever the economic calculations.

Welcome to our new blog conversation on Erika Monahan’s remarkable The Merchants of Siberia: Trade in Early Modern Eurasia (Cornell University Press, 2016). Erika’s book is a comprehensive study of the structure and logistics of trade in Siberia, which is a ground-breaking accomplishment based on considerable archival research. I expect that her analysis of Russia as an “activist commercial state” will become the standard framework for explaining the Russian economy in the future studies. One of the features that is most exciting about the book is that Erika effectively moves between a local history of Siberia and a global view of the Eurasian economy, offering new ideas and interpretations for scholars of Russia and world history.

Welcome to our new blog conversation on Erika Monahan’s remarkable The Merchants of Siberia: Trade in Early Modern Eurasia (Cornell University Press, 2016). Erika’s book is a comprehensive study of the structure and logistics of trade in Siberia, which is a ground-breaking accomplishment based on considerable archival research. I expect that her analysis of Russia as an “activist commercial state” will become the standard framework for explaining the Russian economy in the future studies. One of the features that is most exciting about the book is that Erika effectively moves between a local history of Siberia and a global view of the Eurasian economy, offering new ideas and interpretations for scholars of Russia and world history.

The British expat community found living in Russia to be a great hardship, regularly complaining about the inhospitable weather and its remote location. Even worse, Russia was expensive, especially for prominent foreigners who expected access to some of the finer things. The British envoy to Russia at the beginning of the eighteenth century (Charles Whitworth ) was one of those men. Fortunately, we happen to have access to a couple of his shopping lists (for 1705 and 1706) that provide some insights into the sorts of luxuries a diplomat needed to maintain his position in society. These items were also treated a special project for his staff to acquire, suggesting they weren’t always available in the local markets.

All the items below are on his list from July 1705. In Moscow, Whitworth instructed the British consul to purchase:

6 hogshead of good claret (1 hogshead is about 300 liters)

1 hogshead of good French white wine

1 hogshead of Languedoc or any other good wine

1 or 2 chests of Florence if they are to be procured

1 barrel of English ale

2 dozen drinking glasses

10 dozen of lemons

5 dozen China oranges

A quantity of Dry Sweatmeats

History is being blithely tossed about these days by everyone from Vladimir Putin himself to Sarah Palin and John McCain. What is the real story? Is there a real story?

To answer that question, I invited two eminent historians – well, one historian and one historically minded political scientist, Serhii Plokhii and Mark Kramer, both of Harvard, to speak at MIT on this exact situation. They spoke on Monday (3/17), the day after the Crimean Referendum and the day before the Russian President’s speech.

In October 2010 influential filmmaker Nikita Mikhalkov published an extensive “Manifesto of Enlightened Conservatism” which was published as “Right and Truth” in polit.ru. (Read in Russian here.)

The defense of serfdom attributed to Mikhalkov, which I posted yesterday, may well be a fake, but his conservative views are well-known and worth reading. A shorter overview (and critique) of his Manifesto was published in Vedomosti and translated in The Moscow Times. I am taking the liberty of copying that article in full (below) as it might be interesting for our students in Russian history classes. Lest they (students) think the debates and views of Russian conservatism are archaic, they can see them returning in the extremely conservative new laws on homosexuality, on diversity within the Russian Orthodox Church (the rules on “insulting believers” are very broadly construed), and in the takeover of the Russian Academy of Sciences (long a bastion of independent thinking).

People often say we live in the “nuclear age,” but what that means is never entirely clear. A new documentary produced by a former ABC newsman captures the spirit, or rather spirits, of that era – from its beginnings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and up to the present.

Inspired by the late Cold War, when Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan initiated a process of disarmament in Iceland in 1986, the producer hopes to make viewers believe that eliminating nuclear weapons can happen – despite the growing fatalism and relative inattention to the problem in the post-Cold War era.

As I’ve been working on the history of Russia’s experience with tobacco, I encountered a surprising development – the domestic production of tobacco in Alaska. Anyone who’s spent time working on Russian Alaska could not help to notice the colonists’ continuing concerns about food and agriculture. However, southern Alaska was an agriculturally fertile region, particularly among the Tlingit (on and near Sitka Island) and the nearby Haida. (I’ve been assuming they just didn’t produce the food the Russians wanted, but I could be wrong). Among their products was a type of tobacco (Nicotiana quadrivalis). The mysterious part of the equation is that no one grows N. quadrivalis anymore, and it was native to the southwestern U.S. No one has come up with an explanation about its migration, much less its extermination.

What do we know? The local indigenous groups grew this type of tobacco, and seemed to have consumed it as “chew” – but a particular recipe of tobacco leaf and lime. Though the Russian American Company (RAC) seemed to have been successful in replacing domestic production with imported tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), the mystery for me is why the local population replaced local varieties for an expensive imported variety. Robert Fortuine suggests that it was because the imported version was stronger, but the evidence in only anecdotal, and the mechanism by which indigenous Alaskans acquired it was rather exploitative, to say the least.

In the early years of the Russian American Company, there was an odd incident that led to establishment of three “Russian” forts on the island of Kauai. The reasons for that are somewhat complicated (and the study of several interesting books [1. Most recently, Peter R. Mills, Hawai’i’s Russian Adventure: A New Look at Old History, (Honolulu, 2002)]), but the physical evidence of the venture is the Hawaiian state park at the site of the “Russian” Fort Elizabeth. When I first arrived at the site as a tourist, my first thought was that this was not “Russian” at all.

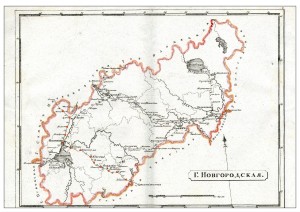

How do you imagine what a road was, historically? Quite often, histories of transport describe histories of surfaces: the evolution of building techniques, say, from wooden planks to macadamized stone to modern asphalt or concrete.

Alternatively, roads are presented as transportation networks or ‘scapes’: that is, as a series of junctures (like the famous Moscow Metro Map) that permit traffic to flow from stop to stop to stop. Yet however important construction- or traffic-based approaches are, one thing they don’t capture is the way that human community is arranged in support of roads, and why. What are the social ‘moorings’ that sustain roads: that service their surfaces and also their travelers, and thereby make transportation along their elaborately constructed landscapes possible at all?

I’ve been trying to visualize an answer to this question, for one of Russia’s most famous roads: the Petersburg-Moscow corridor, in the late 18th century. In what follows, I sketch some initial results; I’d be happy for your thoughts on it.

Having finally finished my biography of Yuri Gagarin (The Cosmonaut Who Couldn’t Stop Smiling: The Life and Legend of Yuri Gagarin, due out in March with Northern Illinois University Press) I’m trying to figure out my next project. This blog presents some very preliminary thoughts about a topic that may occupy my mind for the next number of years. I welcome any thoughts and suggestions.

Extending aspects of my previous book into a later period, I want to investigate the political and cultural significance of transnational manned space flight in the 1970s and 1980s. The beginning point of my project is the Apollo-Soyuz mission in July 1975, which marked both the beginning of a new era of transnational space exploration and an important shift in the political and cultural meanings associated with space flight. Aleksei Leonov, the cosmonaut who participated in the mission, said he was struck again and again during the flight, that “cooperation means friendship, and friendship means peace.” (Hoover Institution and Archives, Association of Space Explorers 1983-85, Box 1, Folder 1.) Cliched statements, for sure, but not, I believe, devoid of genuine belief.