I spent some time this past week preparing for my fall class on the Soviet Union. Each time I’ve taught it here at Hawai’i, I’ve made use of an unique resource at our Library, the “Social Movements Collection,” which is a large group of pamphlets and books that had been collected by Eugene Bechtold, a bookseller and former instructor at the Chicago Workers’ School. While much of the collection relates to American Communism, anarchism, and peace movements, it also contains a rich source of material on the Soviet Union.

Category: Soviet Era 1917-1991

Thanks to Golfo Alexopoulos and Dan Healey for joining the conversation. It is pleasing to see that not only are new young scholars writing about the Gulag, but some of the best established scholars like Golfo and Dan have turned to the subject as well. We still have so much to learn about the operation of this system, and over time all of these scholarly efforts will coalesce into a truly new understanding of the Gulag that will far surpass my own efforts in Death and Redemption. Although I toyed with moving on from studying the Gulag, this plethora of unanswered questions has pulled me back into the subject.

In general, I find the critical responses here as with many earlier responses to emerge to a significant degree from the boldness with which I lay out my argument. In laying out the argument, I will admit to giving up some valuable nuance in favor of an attempt to steer our conversation about the Gulag in new directions. Often, as these respondents repeatedly show, the nuance appears in the heart of the book and at times seems to contradict, or at the very least complicate the bold central argument. At the same time, the respondents seem to value the change in direction of our Gulag conversation above all else.

So many interesting posts in this discussion, I feel like I could write an entire article responding to all of it. Here, I want to try to address some issues brought up initially by Jeff Hardy and in the comments of Wilson Bell (two of the best and brightest among the young Gulag historians) and then expanded on by others. (I must say, also, that Jeff often explains my book’s argument better than I do.) Each writing independent of the other, they raised similar questions about the book’s argument focused on whether and to what extent the “redemption” of the book’s title really matters in practice at the local level. I believe Jeff’s and Wilson’s comments, amplified by others, represent the most spot-on critiques of my book I have ever read and represent what I hope the next generation of Gulag histories will help us better understand.

What I hoped to do with the book, and what I think I have accomplished judging from the collected comments here, was to change the conversation about the Gulag and the role that it played in the Soviet Union. I wanted us to understand the Gulag was much more complex than Anne Applebaum would have it. I wanted us to think about more than the merely repressive or merely economic elements of the Gulag, while never forgetting the repressive and the economic in our analysis. I wanted us to start thinking about the Gulag as a penal system both similar to other modern detention institutions but with its own Soviet particularities.[1. In this, I stand on the shoulders of giants, following a raft of scholarship from the last twenty years that pushed us to see late imperial Russia and the Soviet Union as part of the broader Euro-American development of a modern political system rather than something sui generis, while maintaining sensitivity to the particularities of the Russian/Soviet version of this modernity.] When we learned in the late 1980s and early 1990s that a huge percentage of the Gulag population was released every year and that a minority of Gulag prisoners were politicals, previous explanations for the Gulag’s role in the Soviet Union seemed, if not wrong, certainly incomplete. Understanding what these new facts meant for our understanding of the Gulag has driven my research for more than a decade. Who was released, and when, and why? Who was not released? Did Soviet authorities care what became of the millions who would spend time in the camps but then return to Soviet society?

First, I must thank my colleague and co-blogger Andrew Jenks for setting up this blog conversation here at Russian History Blog. As an academic author, I have found the wait for journal reviews of my book to be excruciating. The book came out almost exactly one year ago, and the first two reviews of the book appeared only in the last month. (Only this French review is available on the free web.) Immediacy is definitely something the blog conversation can uniquely provide.

It is a great honor to have this stellar cast gathered for this conversation. I find the praise overwhelming and flattering (“dean of Gulag studies“? wow!) and the critiques painful but also exhilarating and thought-provoking. Most of all, I am excited to see that the argument I tried to make in the book (warts and all) actually came through to the readers.

In an effort to facilitate this as “conversation”, I’ll respond intermittently to the readers’ comments rather than waiting for all to chime in. Here, I want to address the issue of images raised both by Deborah Kaple and Cynthia Ruder. Obviously, I can change nothing about the book now and I acknowledge that the book would have been improved with more images, but I can point now to some visual (and textual) evidence that might be useful to readers and to all of our students. I like Cynthia’s idea of creating auxiliary web material for the book, and it’s something I’ll think about doing. However, I would point out the availability of some freely available auxiliary material that may not be known to all. (For an extended discussion of materials available for teaching the Gulag, look at the posts by Wilson Bell and me at Teach History, Karl Qualls’ blog on teaching Russian history.)

I would point readers and students to the Gulag website created with my colleagues at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media here at George Mason University. In addition to a virtual exhibit, complete with visually-based original mini-documentaries, the site, especially in its archive, contains a wealth of visual evidence.The text search and the “browse by tag” function allows one to find materials by location, subject matter, person, etc.

In particular and in relation to Death and Redemption, I would like to point colleagues, readers, and students with Russian language skills to a selection of documents from the local Karlag archive in Karaganda.

As for a map of Karlag, it is easier said than done. Karlag, like most Gulag camps, did not occupy a single defined (let alone enclosed) space. It was diffuse with many different sub-camps located around the steppe of central Kazakhstan (not to mention the many “de-convoyed” prisoners who were herding animals around the steppe without residing in a particular camp zone and sometime even without the presence of an armed guard.) I try to describe the extent of the camp in the text by pointing out its outermost sub-camps, and I provided a map that located the most important geographic locales in Kazakhstan discussed in the book. To draw lines around the camp would be misleading as to how the camp was actually organized. (Here is a rather poor-quality version with credit to the cartographer Stephanie Hurter Williams.)

Though still a relatively young scholar (nine years since receiving his Ph.D.), Steve Barnes can rightfully be considered the dean of Gulag studies in the United States. From his provocative 2003 dissertation, to his Gulag: Many Days Many Lives website, from his many public talks to his mentoring of other scholars, Steve has been at the forefront of all things Gulag over the past dozen years. He organized a conference devoted to new interpretations of the Gulag, he helped facilitate a traveling Gulag exhibition put on by the National Parks Service and Gulag Museum in Perm, he has authored several scholarly articles, and his current slate of projects includes several devoted to Gulag themes. I therefore consider it a privilege to review his latest and most important work, which is in my mind the most significant book on the Gulag since Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago. On the surface, it has much to recommend it against other works on the Soviet penal system. It covers the entire Stalin era, plus a little beyond. It is a detailed study of one location—Karlag—but it employs evidence from across the Gulag. It is based evenly on archival and memoir sources, both of which are necessary to understand the Gulag phenomenon. It covers a range of penal institutions. And it explores both the theory and the practice of punishment in the Soviet Union.

The primary contribution of Death and Redemption is the author’s willingness to ask (and, of course, answer) a seemingly simple question: Why did the Soviet authorities spend enormous amounts of energy and resources “to replicate the Soviet social and cultural system within the Gulag?” In other words, why not just kill the prisoners either through execution or through penal labor and use the resources on any number of other important priorities, rapid industrialization being chief among them. Why go to such lengths to try to reform them into good Soviet citizens? Certainly, millions of Soviet subjects were shot or worked to death in the camps of the Gulag, or left to die in the so-called special settlements. But several times more survived confinement and returned to Soviet society having supposedly undergone the process of “reforging” or “re-education.” To some this re-education process was a farce, lip service to Bolshevik identity that prisoners simply ignored or manipulated to their own advantage. Barnes, while not dismissing such reactions to the re-education process, nonetheless accepts it as real, as tangible evidence that the Gulag represented not just the fears of Soviet socialism but its hopes and dreams as well. Indeed, he views it as a crucial link for understanding in their full complexity the tensions inherent in the Soviet worldview, and, more narrowly, in their vision of criminal justice in a socialist society.

This understanding of the Gulag as a microcosm of Soviet society, with events, institutions, and relationships in the Gulag mirroring those outside the barbed wire, owes much to Solzhenitsyn, as Barnes readily acknowledges. Yet Barnes views this not as an exclusively negative, repressive phenomenon as Solzhenitsyn does, but as a positive, constructive one. It was perhaps not a moral system, but it operated within its own system of ethics that made sense to its practitioners. From political indoctrination sessions to socialist slogans in the barracks, from literacy classes to musical performances, Gulag life was organized around this new socialist ethos. And the most important part of this ethos and of Gulag life was labor. It was the primary method and indicator of re-education, of the inmate’s readiness to return to a productive life outside the barbed wire. Those who failed this critical test could have no place in Soviet society—they were slated for death.

For Barnes the tension between life and death, between redemption and guilt is summarized in this visual propaganda piece, which is described but unfortunately not included in the book:

Here a mock grave complete with coffin has been constructed for members of a prisoner labor brigade. The crime, as depicted by several signs, each bearing a prisoner’s surname along with a percent—22%, 30%, 42%—was underperformance of the work quota. Laziness. The message is unmistakable: those who do not perform their labor duty are not submitting to re-education. They will exit the Gulag not by release but by death. Or as Barnes puts it: “In the harsh conditions of the Gulag, the social body’s filth would either be purified (and returned to the body politic) or cast out (through death).” (14) What is important here is that both options—death and redemption—are appealing outcomes in the Soviet worldview. Setting deadly violence alongside correction was not a contradiction, but an ideal. It was not a perversion of socialism, it was not some sort of Stalinist deviation, it was how socialism was to be built. This argument is the central tenet of the book and a significant departure from most other works on the Gulag, from Solzhenitsyn’s and Anne Applebaum’s memoir-based studies, to the more archivally-grounded works of Oleg Khlevniuk and Galina Ivanova. It is also an important theoretical foundation on which younger scholars, including myself, can build.

I hope I made it clear that I consider The Stalin Cult an excellent work of political and institutional history, from which I learned a great deal about a subject I care about. But my objections to its treatment of the visual culture so central to Stalin’s personality cult do not end with circles. And I do like a good argument. (Can I blame my parents? I grew up in household where arguing about ideas was a sign of love and respect.) Plamper’s discussion of individual works of art may, as he put it, “borrow tools from contemporary visual studies,” but it does so rather unevenly. The result is a book that deserves all the praise it has received from the other bloggers, who largely ignored the visual, but it doesn’t give us a proper sense of the visual culture that made up the cult or the visual experience of living in it.

Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Mao Zedong, Kim Jong-Il, Joseph Stalin. The mere sound of these names conjures up mental images of the personality cult–films, monuments, renamed cities, prose, poetry, and, perhaps most of all, portraiture all designed to raise a dictatorial leader to mythic, super-human status. All Russian history professors teach about the Stalin cult, and students find it endlessly fascinating, yet surprisingly little serious academic research has been devoted to the topic–until now. Yale University Press has just published Jan Plamper’s The Stalin Cult: A Study in the Alchemy of Power, and we have brought in a terrific group of experts to discuss what is, in my estimation, an instant classic in the field of Russian history.

Since we held our first blog conversation on Gulag Boss in the fall, we have received a lot of positive feedback on the format and hope to make this a regular feature here at Russian History Blog. (You can read my initial thoughts on the form of the blog conversation.) Periodically, either my co-bloggers or I will pick a book (new or old) or a topic, bring in guest bloggers with appropriate expertise, and invite our readers to participate via commenting on the individual posts. From time to time, we hope to coordinate our efforts with the New Books Network, as we have done for this conversation. Sean Guillory, host of New Books in Russian and Eurasian Studies interviewed Plamper about the book and I urge you to listen to the podcast and join us for the conversation here at the blog. I also hope you will become a regular at New Books in Russian and Eurasian Studies where many an author, myself included, are given the opportunity to talk about our works.

Since we held our first blog conversation on Gulag Boss in the fall, we have received a lot of positive feedback on the format and hope to make this a regular feature here at Russian History Blog. (You can read my initial thoughts on the form of the blog conversation.) Periodically, either my co-bloggers or I will pick a book (new or old) or a topic, bring in guest bloggers with appropriate expertise, and invite our readers to participate via commenting on the individual posts. From time to time, we hope to coordinate our efforts with the New Books Network, as we have done for this conversation. Sean Guillory, host of New Books in Russian and Eurasian Studies interviewed Plamper about the book and I urge you to listen to the podcast and join us for the conversation here at the blog. I also hope you will become a regular at New Books in Russian and Eurasian Studies where many an author, myself included, are given the opportunity to talk about our works.

My university (California State University, Long Beach) is screening a number of documentary films about Russia this semester, including three films from the esteemed documentary film maker Marina Goldovskaya: A Taste of Freedom (1991, 46 min.), A Bitter Taste of Freedom (2011, 88 min.), and Three Songs About Motherland (2009, 39 min.) Goldovskaya will be attending the event on this March 18 — and I will be participating in a panel discussion along with a number of other professors. So if you are in the LA area please do attend. Venue and details about this and other events can be found here: http://bwordproject.org/

Here is my review of one of the films, Three songs About Motherland. I have found it especially valuable for the classroom because of its brevity and neat division into three compelling stories.

I’ve been reviewing documents from the Hoover Archives in connection with my latest project (https://russianhistoryblog.org/2011/10/transnational-history-and-space-flight/). The ones I’ve posted here, with brief commentary and historical context, concern an organization of astronauts and cosmonauts called the Association of Space Explorers, which held its first Congress in Paris in October 1985.

The idea for the group emerged during informal conversations between cosmonauts and astronauts dating back to the Apollo-Soyuz mission in 1975 — that “memorable handshake in space,” as the world press at the time put it. The end of detente, however, got in the way, first with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, followed by the U.S. boycott of the Moscow Summer Olympics, the Soviet boycott four years later of the Los Angeles games, Reagan’s announcement of the Star Wars program in March 1983, and the Soviet shooting down of a South Korean jet airliner in September 1983.

This 2010 documentary, which has deservedly gotten a lot of press, is well worth showing to students (http://desertofforbiddenart.com/). It follows a treasure trove of Russian art stashed in a remote desert region of Uzbekistan known as Karakalpakstan, where the art was hidden from Soviet censors. Getting there required crossing a vast desert—punctuated by breaks at fly-infested truck stops. Nukus was the principal city of this desert outpost and the location of the museum housing this unlikely art collection. The art was forbidden, not because the artists were consciously anti-Soviet, but because they simply followed their own muses, irrespective of the dictates of the official Soviet artistic style under Stalin.

That such a collection of astounding avante-garde art could exist in Nukus amazed a New York Times reporter, who happened upon the museum during his time as a foreign correspondent covering Uzbekistan after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

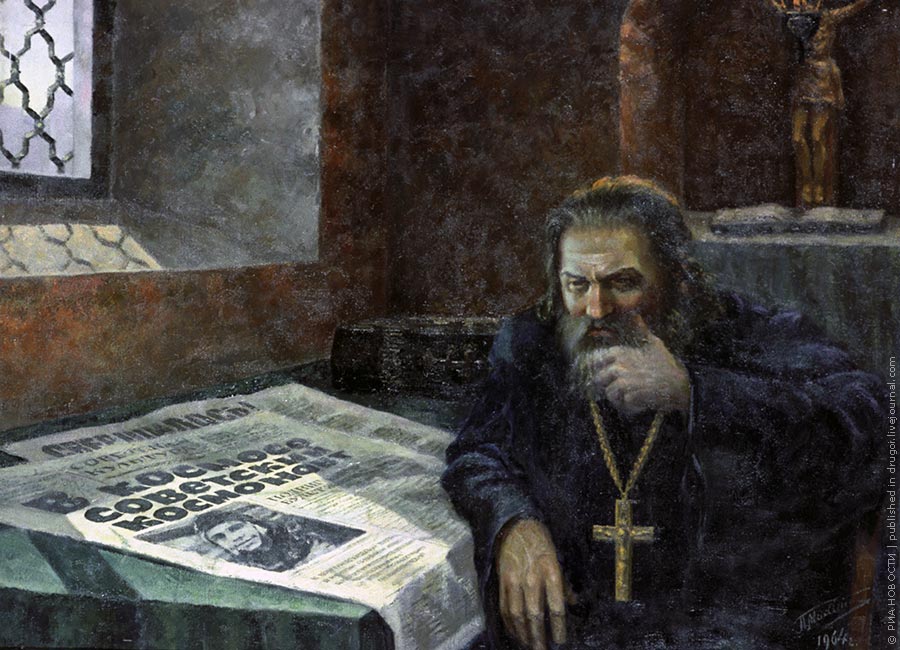

Here is a painting entitled “Meditation,” which was done in 1964 by Pyotr Mikhailov. It is from the old Leningrad Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. In it a priest contemplates Gagarin’s flight into space. What is not clear to me, however, is just what this piece of official art would have conveyed to viewers. It hardly seems like a straightforward piece of atheist propaganda, or does it?

Here is a painting entitled “Meditation,” which was done in 1964 by Pyotr Mikhailov. It is from the old Leningrad Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. In it a priest contemplates Gagarin’s flight into space. What is not clear to me, however, is just what this piece of official art would have conveyed to viewers. It hardly seems like a straightforward piece of atheist propaganda, or does it?

Having finally finished my biography of Yuri Gagarin (The Cosmonaut Who Couldn’t Stop Smiling: The Life and Legend of Yuri Gagarin, due out in March with Northern Illinois University Press) I’m trying to figure out my next project. This blog presents some very preliminary thoughts about a topic that may occupy my mind for the next number of years. I welcome any thoughts and suggestions.

Extending aspects of my previous book into a later period, I want to investigate the political and cultural significance of transnational manned space flight in the 1970s and 1980s. The beginning point of my project is the Apollo-Soyuz mission in July 1975, which marked both the beginning of a new era of transnational space exploration and an important shift in the political and cultural meanings associated with space flight. Aleksei Leonov, the cosmonaut who participated in the mission, said he was struck again and again during the flight, that “cooperation means friendship, and friendship means peace.” (Hoover Institution and Archives, Association of Space Explorers 1983-85, Box 1, Folder 1.) Cliched statements, for sure, but not, I believe, devoid of genuine belief.

Princeton University Press published my book, Death and Redemption: The Gulag and the Shaping of Soviet Society in May. I had the great pleasure to talk about the book with Sean Guillory (of Sean’s Russia Blog) at New Books in Russian and Eurasian Studies.

I’ve just seen an engaging 2010 documentary entitled the “Russian Concept” (for a trailer see: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0-l66s2Fglk). Based on interviews with artists, art collectors and esteemed art historians, the documentary provides a short and entertaining survey of art little known to Western college students. Its subject matter is primarily unofficial – and sometimes persecuted – art from the Soviet era, much of it purchased by the art collector Norton Dodge (who smuggled 10,000 art works out of the Soviet Union during the Cold War, earning him the nickname the “Lorenzo de Medici” of Russian art). But it also examines the fate of art in Russia following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Over the Easter weekend, I was reading The Guardian and came across a full-page photograph taken by Henri Cartier-Bresson on a visit to the Soviet Union in 1954. This stunning photograph was used the following year as the front cover of Life magazine.

Over the Easter weekend, I was reading The Guardian and came across a full-page photograph taken by Henri Cartier-Bresson on a visit to the Soviet Union in 1954. This stunning photograph was used the following year as the front cover of Life magazine.

To me the image is of a balmy Moscow day. Two pretty young girls are being eyed up by soldiers. People are waiting for a trolley-bus to take them home. A man is selling ice-cream, or maybe kvass, in the background.

Today marks the 66th anniversary of Victory Day. As Sean Guillory notes in a must-read post, victory, like so many other aspects of 20th century east European history, is remembered quite differently in many post-Soviet and post-Communist states. He writes:

Russia, with much justification, views this transformation of the memory of liberation into the memory of conquer as deeply insulting. Yet the whether one thinks about the legitimacy of these moves, they nevertheless raise some quite uncomfortable questions about the basis for history, memory and identity. How to reconcile all these memories of victimhood into a general narrative, where the field of victims in the war can be objectively be dispersed between the war’s winners and losers? Can it be done? Should it? Or is the European memory of the war, as Tony Judt suggests, ever to remain “deeply asymmetrical”?

Of course, it is not only in Russia where the war is fondly remembered and revered as unsullied victory. In addition to the beautiful sand art animation from Ukraine’s Got Talent that I shared previously, I can’t help but think of this video, which I frequently show to my post-1945 Soviet/post-Soviet history students. It was made for the 60th anniversary of Victory Day in Karaganda, Kazakhstan. It is another great way to get my students to think about the different degree to which World War II continues to matter in the United States versus the former Soviet Union (obviously, as Sean highlights for us, this memory is not always positive). All you have to do is pick the latest favorite hip hop artist and ask the students if they could imagine them rapping about World War II.

The recent nuclear disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi brought the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown back into an often forgetful public consciousness. Although we will no doubt soon forget these events again, especially amidst the insane amount of coverage focused on royal nuptials, the world press is taking some note of Chernobyl today–the 25th anniversary of the disaster. A search on Google news shows over 9,400 articles referencing Chernobyl in the last 24 hours. The articles run the gamut: human interest stories (see also here), reminiscences from those who lived near Chernobyl and from the leaders who had to deal with the disaster, and a panoply of stories on how Chernobyl affected this or that locality. Although the Washington Post presented Chernobyl as the key to Ukrainian independence, coverage of the 25th anniversary differs significantly from the 20th in 2006. Then, many articles stressed Chernobyl’s role in the Soviet collapse. Although such stories are not entirely absent this year, ties to Fukushima Daiichi and anti-nuclear protests dominate the headlines (along with Russian President Dmitrii Medvedev’s trip to Chernobyl to mark the anniversary.) Nature magazine, I should add, has some important extensive coverage of the event.

The recent nuclear disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi brought the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown back into an often forgetful public consciousness. Although we will no doubt soon forget these events again, especially amidst the insane amount of coverage focused on royal nuptials, the world press is taking some note of Chernobyl today–the 25th anniversary of the disaster. A search on Google news shows over 9,400 articles referencing Chernobyl in the last 24 hours. The articles run the gamut: human interest stories (see also here), reminiscences from those who lived near Chernobyl and from the leaders who had to deal with the disaster, and a panoply of stories on how Chernobyl affected this or that locality. Although the Washington Post presented Chernobyl as the key to Ukrainian independence, coverage of the 25th anniversary differs significantly from the 20th in 2006. Then, many articles stressed Chernobyl’s role in the Soviet collapse. Although such stories are not entirely absent this year, ties to Fukushima Daiichi and anti-nuclear protests dominate the headlines (along with Russian President Dmitrii Medvedev’s trip to Chernobyl to mark the anniversary.) Nature magazine, I should add, has some important extensive coverage of the event.

Most of us, no doubt, teach about Chernobyl in our Soviet history courses. I wanted also to share two phenomenal resources for helping our students understand that horrible event. First, thanks to a number of colleagues for pointing out these chilling photographs taken at the time of the event. Second, I wanted to share a video that always helps students understand the magnitude of the tragedy. The French organization IRSN which focuses on nuclear safety issues provides this frightening video showing the spread of radioactive contamination during the two weeks immediately following the accident.

UPDATE

Thanks to the Davis Center at Harvard for pointing out After Chernobyl, an amazing resource on life around Chernobyl since the accident.

So, this week’s YouTube of the Week is perhaps of more interest to researchers than it is to students. This is just part one of a series of videos uploaded by the Iowa State University Library’s Special Collections. They include raw news footage of Nikita Khrushchev’s 1959 visit to Iowa. I have not yet watched all of the footage, but in the midst of a lot of dullness, many great moments and images often tell you more about American history than Soviet. Of particular interest are the Iowans lining the roads for Khrushchev’s motorcade and holding up signs, including slogans like “The Only Good Communist is a Dead Communist.”

Unfortunately, it seems the ISU Library has disabled the capacity to embed the video in a blog post, so you’ll have to go here. Khrushchev in Iowa

As I noted in my first post (“Creating Cover Stories: A National Pastime”), an intense feeling of vulnerability and insecurity had compelled the Soviets, along with Russia’s authoritarian traditions, to surround Yuri Gagarin’s flight in secrecy. But they paid for their secret ways in the coin of rumor — a legacy that survives as the world celebrates the fiftieth anniversary of Gagarin’s flight this April 12. As a noted geographer once remarked: “When we wonder what lies on the other side of the mountain range or ocean, our imagination constructs mythical geographies.” Gagarin’s flight and life were (and will forever be) a mythical geography.[1]

To navigate the mythical realms of Gagarin’s flight I have analyzed special summaries of foreign press reports (located in the State Archive of the Russian Federation). Those summaries, with occasional commentary, were provided by Soviet analysts. Those analysts systematically sampled the foreign press, and also the climate in the Moscow press corps, for reactions to Soviet space exploration. The target audience for these reports was apparently the political leadership as well as managers of the Soviet space program.

When I began my study of Yuri Gagarin many years ago, my biggest challenge, as any historian who has worked in Russian archives can appreciate, was getting access to sources. Gagarin was and remains not just a Soviet icon — but a Russian icon, manipulated and exploited for various patriotic purposes by Soviet and post-Soviet governments. That is especially the case with the fiftieth anniversary of Gagarin’s flight less than two weeks away. Vladimir Putin has personally chaired the organizing committee for celebrations. Relatives, cosmonauts, government officials, museum workers, and curators have arranged the proverbial wagons around Gagarin to protect him from any attempt to tarnish his image — either those based on historical evidence or those concocted from urban myth and hearsay (the main source of information about Gagarin for many journalists, as noted in my previous blog).