The continuum of images in Asif’s last post attests to the emergence of a distinct visual vocabulary of space flight long before it became a reality. It is not coincidental that the first of these images is from Yakov Protazanov’s Aelita, a 1924 film that enthralled moviegoers but left official critics scratching their head. In “Imagining the Cosmos,” Asif situated the film’s ideological complexity as well as its striking visuals within an astonishingly diverse network of early-twentieth-century cosmic enthusiasm. Here I would like to think about a different set of relations between cinema and the cosmos, based not so much on modes of representation but rather on the fundamental convergences between the process of making movies and the “co-production of imagination and engineering” long before space flight became a reality. The interface between engineering and imagination underlying the very apparatus and materiality of the cinematic medium — which becomes particularly visible in special effects — links the history of Soviet space culture with the spectacular pre-histories of its future projected on the big screen.

Category: Soviet and Russian Space Flight

As this week closes, I wanted to highlight that seems somewhat obvious to those with even a casual interest in the history of Russian/Soviet space activities, its incredibly rich visual record. The picture that Andy posted of cosmonaut Shatalov meeting Native Americans in the U.S. in 1974 is one perfect example of that record. I’m posting here 6 images from the pre-Sputnik era which I think capture interesting moments in this long and rich history with appropriate captions. I’ll post some images from the 1960s and 1970s in a separate post.

In a comment to my last posting, Asif noted that in “group photos of Soviet engineering teams from the 1950s and 1960s involved in the space program, there are a surprisingly high number of women in the pictures, surprising given their near-absence in the cosmonaut corps.” He wondered how many women in the 1950s and 1960s were, in fact, involved in science and engineering fields.

As I noted in previous publications, the 1970 all-union census reported that more Soviet women than ever before were engineering-technical workers, their number more than doubling in ten years from 1.63 to 3.75 million.[i] Women’s influence in science and technology was evidenced, too, by increases in the number of higher degrees they earned in science, engineering, and technology fields. Official statistics published in 1975 confirmed that the number of female researchers among science personnel in the USSR had increased dramatically in the post-war period, from 59,000 in 1950 to just shy of 129,000 in 1960 to nearly 465,000 in 1974.[ii] That said, a 1971 study that broke down female accomplishment by branch of science showed that women in physics and math still lagged considerably behind men in the attainment of advanced degrees.[iii] And yet, it is significant to note that three out of four women awarded candidate and doctoral degrees in the 1971-73 period were in the natural and applied sciences.[iv]

This is in response to an interesting comment on my earlier post regarding the stamp image I used, which commemorated Aleksei Leonov’s 1965 space walk (https://russianhistoryblog.org/2013/12/russian-space-history-transnational-culture-and-cosmism/#comments). The comment noted differences between the United States and the Soviet Union. Not only was the Soviet Union more concerned with celebrating space feats on stamps, but Soviet cosmonauts were themselves directly involved in the creation and promotion of those stamps. After his flight Gagarin wrote an article on the theme of cosmonauts on stamps and carried on a correspondence with avid philatelists. Leonov, the cosmonaut-artist, actually drew the images that appeared on many cosmonaut-themed stamps (yet another illustration of how the cosmonauts promoted themselves above and beyond official state promotion).

Cosmonautics was also celebrated on coins issued for various jubilees of Soviet space accomplishments. I’m not aware, though it is far from my specialty, of the extent to which American astronauts appeared on coins, if at all. With regard to the celebration of Soviet cosmonautics in various media Cathleen Lewis at the Air and Space Museum has done quite a bit of work.

In an oft-quoted remark, Svetlana Boym asserted that “Soviet children of the 1960s did not dream of becoming doctors and lawyers, but cosmonauts (or, if worse came to worst, geologists.” [1. Svetlana Boym, “Kosmos: Rememberences of the Future, in Kosmos: A Portrait of the Russian Space Age, Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001, 83.] This illustration from a December 1960 issue of the children’s magazine, Murzilka, suggests that even before Yuri Gagarin’s leap into the cosmos, Soviet children’s culture was compelling the USSR’s youngest citizens to commit their dreams to the stars.

In an oft-quoted remark, Svetlana Boym asserted that “Soviet children of the 1960s did not dream of becoming doctors and lawyers, but cosmonauts (or, if worse came to worst, geologists.” [1. Svetlana Boym, “Kosmos: Rememberences of the Future, in Kosmos: A Portrait of the Russian Space Age, Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001, 83.] This illustration from a December 1960 issue of the children’s magazine, Murzilka, suggests that even before Yuri Gagarin’s leap into the cosmos, Soviet children’s culture was compelling the USSR’s youngest citizens to commit their dreams to the stars.

As Monica Rüthers pointed out in a recent article, in the aftermath of Sputnik and Gagarin, the twin catapults of celebrity and propaganda bombarded children with irresistible images of success and personal possibility: “The strong and meaningful motifs of ‘childhood’ and ‘cosmos’ were used in combination,” Rüthers argues. “In their symbolic meaning, these iconographic motifs signified the belief in the country’s leading role in the future of mankind.” [2. Monica Rüthers, “Children and the Cosmos as Projects of the Future and Ambassadors of Soviet Leadership,” in Eva Maurer, et. al., eds., Soviet Space Culture: Cosmic Enthusiasm in Socialist Societies, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, 206.]

In his initial posting to this conversation, Asif Siddiqi asked us to consider (among other things) “the co-production of imagination and engineering in Soviet space culture” and, more specifically, “the challenges of drawing connections between popular discourse and real world changes.” When it came to imagining their future selves, at least some among the first generation of space age children believed that they were living in a time and place where their dreams would come true. Consider the following excerpt from a letter written to Valentina Tereshkova by a girl in Irkutsk oblast:

I just finished the 4th grade, so at the moment I can’t think about a flight to the cosmos. Your deed made me very glad. I hope that when I grow up the success of our science and technology will stride far beyond the limits of outer space and in time no doubt there will be a flight for tourists to other planets. How fortunate that I live in this century, when my native people are capable of space flight and I know that my dream will also come true. [3. RGAE, f. 9453, op. 2, ed. khr. 151, p. 46-46ob]

In balmy Culver City near Los Angeles, not far from the campus where I teach, there is a wonderful little museum called the Museum of Jurassic Technology (http://mjt.org/). The museum contains a Russian tea room and aviary on the roof. Next to the Russian tea room are two exhibition halls. One contains portraits of all the Soviet space dogs. Another is devoted to the life and myth of Konstantin Tsiolkovskii, whose translated technical works as well as science fiction are available in the museum gift shop. I often thought about that exhibit –and how odd it must be for casual visitors — as I worked about 40 miles to the south, in the place where Richard Nixon grew up, at the Nixon library and archives.

I am not sure what provoked the outpouring of scholarship on the history of Soviet space culture over the past decade or so. Was it part of the cultural “turn” that historians of the post-Stalin decades started to take in the 1990s? Did it have something to do with what historians of American space technology were writing? Or was the inspiration more proximate – maybe Vail and Genis’ chapter on the kosmos from their book on the Soviet sixties, originally published in 1988 but not immediately well known? Whatever its origin, the abundance of riches surely is a remarkable development. It is, among other things, transnational – the 23 authors who have contributed to these four books work in nine different countries. It also varies in emphasis and focus – pioneers and projects; myth and reality; gender, regional, and international political dimensions.

I am very excited to kick off the seventh conversation on the Russian History blog on the topic of Soviet/Russian space history. Instead of the usual focus on one monograph, we are using a number of recent texts that recover, explore, and rethink the intersections between “cosmic enthusiasm” (as the title of one of the books characterizes it) and Soviet/Russian culture. These are two individually authored monographs: my own The Red Rockets’ Glare: Spaceflight and the Soviet Imagination (Cambridge University Press, 2010) and Andrew Jenks’ The Cosmonaut Who Couldn’t Stop Smiling: The Life and Legend of Yuri Gagarin (Northern Illinois University Press, 2012), and two edited books that have some overlap: Eva Maurer, Julia Richers, Monica Ruthers, and Carmen Scheide, eds., Soviet Space Culture: Cosmic Enthusiasm in Socialist Societies (Macmillan, 2011) and James T. Andrews and Asif Siddiqi, eds., Into the Cosmos: Space Exploration and Soviet Culture (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012).

I am very excited to kick off the seventh conversation on the Russian History blog on the topic of Soviet/Russian space history. Instead of the usual focus on one monograph, we are using a number of recent texts that recover, explore, and rethink the intersections between “cosmic enthusiasm” (as the title of one of the books characterizes it) and Soviet/Russian culture. These are two individually authored monographs: my own The Red Rockets’ Glare: Spaceflight and the Soviet Imagination (Cambridge University Press, 2010) and Andrew Jenks’ The Cosmonaut Who Couldn’t Stop Smiling: The Life and Legend of Yuri Gagarin (Northern Illinois University Press, 2012), and two edited books that have some overlap: Eva Maurer, Julia Richers, Monica Ruthers, and Carmen Scheide, eds., Soviet Space Culture: Cosmic Enthusiasm in Socialist Societies (Macmillan, 2011) and James T. Andrews and Asif Siddiqi, eds., Into the Cosmos: Space Exploration and Soviet Culture (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012).

The appearance of these texts (as well as many other books and essays on Soviet space culture in the past few years) suggests that academic interest in the topic has attained a critical mass that warrants some self-reflection. Before we launch this exchange, I wanted to introduce and frame the topic and then raise a few pertinent questions to serve as a catalyst towards more in-depth discussion.

Many thanks to Alexander Geppert, a leading figure in the history of space flight and European culture, for this review of two recent volumes on Russian space flight and culture (in which I and fellow blogger Asif Siddiqi have essays). It’s nice to see a scholar from outside our field address our scholarship.

http://hsozkult.geschichte.hu-berlin.de/rezensionen/type=rezbuecher&id=17657

What I find most interesting about this outsider’s perspective is that it confirms something that many of us perhaps already know – or should know: the parochial nature of our scholarship and scholarly community (as an aside, it’s great that the Russian History Blog has included scholars from outside the Russian field to comment on our scholarship in the Blog Conversations). The point was driven home to me at the April 2012 conference in Berlin put on by Alexander (http://hsozkult.geschichte.hu-berlin.de/tagungsberichte/id=4303). I was the lone Russianist at the conference. I was struck by the marginalization of Russia in the European context (even as the papers devoted to the United States, in a conference dedicated to European visions of space and utopia, dominated parts of the agenda). I think we Russianists share some of the blame for this, precisely because of our tendency to eschew transnational or global approaches to writing the history of Russia and the Soviet Union in the 20th century. But what would a transnational history of space flight and culture look like? It’s a question that consumes me now as I attempt to research the space race in a transnational context — focusing on collaborative moments such as the Apollo-Solyuz Test Project, the Interkosmos flights beginning in 1979, the Association of Space Explorers in the 1980s, and the Mir and ISS space stations. If anyone feels so inspired, perhaps they could point me to interesting examples of attempts to write Cold War Russia and the Soviet Union into a more global — or at least — pan-European history.

Here is a first review of my new book on Yuri Gagarin. http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2109/1

The publication is read by space enthusiasts and engineers and managers in the space business. I like the fact– which was partly my hope in publishing this book — that the book would reach non-academics as well as the usual academic market of 300 or so libraries and various interested historians and specialists. Just a few weeks ago I gave a talk on my book to the Boeing Defense and Space Systems group in Seal Beach California. The audience consisted of executives and managers in Boeing’s space and defense operations. Many had visited Russia to work with their counterparts in the Russian space business. They provided a unique, non-academic perspective on my topic — yet they were also receptive to many of the same problems that professional Russian historians grapple with in their work: issues of identity, cause and effect, the politics of gender, class, and race, etc.

I’ve been reviewing documents from the Hoover Archives in connection with my latest project (https://russianhistoryblog.org/2011/10/transnational-history-and-space-flight/). The ones I’ve posted here, with brief commentary and historical context, concern an organization of astronauts and cosmonauts called the Association of Space Explorers, which held its first Congress in Paris in October 1985.

The idea for the group emerged during informal conversations between cosmonauts and astronauts dating back to the Apollo-Soyuz mission in 1975 — that “memorable handshake in space,” as the world press at the time put it. The end of detente, however, got in the way, first with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, followed by the U.S. boycott of the Moscow Summer Olympics, the Soviet boycott four years later of the Los Angeles games, Reagan’s announcement of the Star Wars program in March 1983, and the Soviet shooting down of a South Korean jet airliner in September 1983.

My man Yuri Gagarin gets another Russian coin from the Russian Central Bank in honor of the flight’s 50th anniversary last April. He remains one of the few official Soviet heroes to merit being put on a post-Soviet piece of Russian currency. As I tell my students, if you want to know what people consider important, look at what they put on their money.

http://vz.ru/photoreport/542796/

Adding to the previous thread of comments about Gagarin and religion, perhaps the most striking amendment to the Gagarin legend since the collapse of the Soviet Union has been his re-imagination as a devout Russian Orthodox Christian. I often heard from Gagarin’s acquaintances and Gagarin museum officials that Gagarin was secretly a believer.

Adding to the previous thread of comments about Gagarin and religion, perhaps the most striking amendment to the Gagarin legend since the collapse of the Soviet Union has been his re-imagination as a devout Russian Orthodox Christian. I often heard from Gagarin’s acquaintances and Gagarin museum officials that Gagarin was secretly a believer.

New legends also emerged about Gagarin’s efforts to save local churches from being blown up during Soviet anti-religious campaigns. “He did not reject God!” proclaimed a local poet in a poem entitled “Faith.” If Gagarin was a kind of Jesus, his mysterious death in a 1968 plane crash (at the age of 34, just like Jesus) was a test of faith, an act of sacrifice that challenged Russians to consider their sinful nature and united them in grief. Said another poet from his hometown: “He gave his life for us/So that people would remember and value him…Oh, how my dove of peace circles overheard!/Over Gzhatsk he will fly for all eternity.” (Gzhatsk-Gagarin. 300 Let: Stikhi, poemy, pesni [Moscow: Veche, 2007], 83-84.)

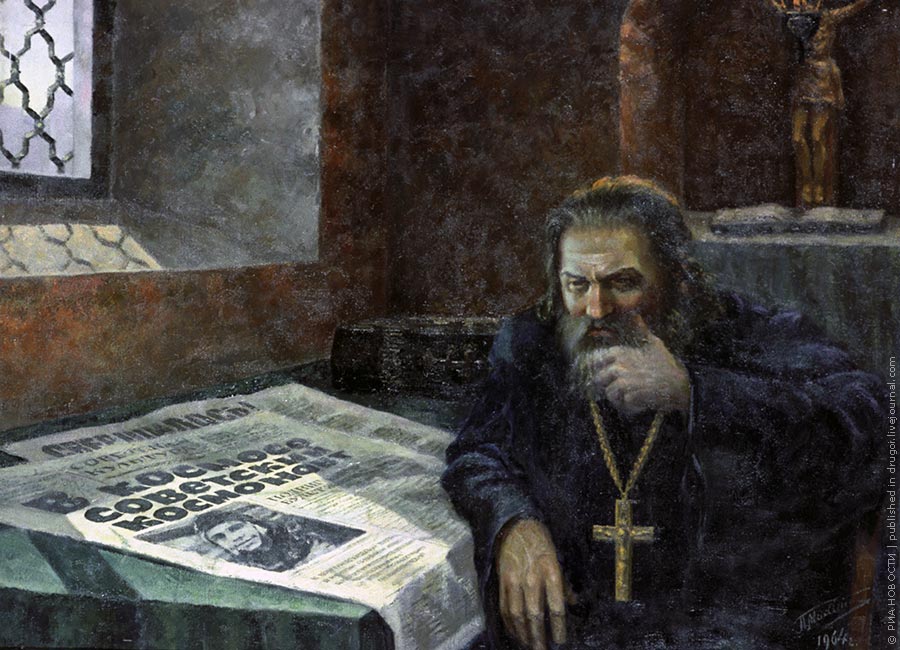

Here is a painting entitled “Meditation,” which was done in 1964 by Pyotr Mikhailov. It is from the old Leningrad Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. In it a priest contemplates Gagarin’s flight into space. What is not clear to me, however, is just what this piece of official art would have conveyed to viewers. It hardly seems like a straightforward piece of atheist propaganda, or does it?

Here is a painting entitled “Meditation,” which was done in 1964 by Pyotr Mikhailov. It is from the old Leningrad Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. In it a priest contemplates Gagarin’s flight into space. What is not clear to me, however, is just what this piece of official art would have conveyed to viewers. It hardly seems like a straightforward piece of atheist propaganda, or does it?

Having finally finished my biography of Yuri Gagarin (The Cosmonaut Who Couldn’t Stop Smiling: The Life and Legend of Yuri Gagarin, due out in March with Northern Illinois University Press) I’m trying to figure out my next project. This blog presents some very preliminary thoughts about a topic that may occupy my mind for the next number of years. I welcome any thoughts and suggestions.

Extending aspects of my previous book into a later period, I want to investigate the political and cultural significance of transnational manned space flight in the 1970s and 1980s. The beginning point of my project is the Apollo-Soyuz mission in July 1975, which marked both the beginning of a new era of transnational space exploration and an important shift in the political and cultural meanings associated with space flight. Aleksei Leonov, the cosmonaut who participated in the mission, said he was struck again and again during the flight, that “cooperation means friendship, and friendship means peace.” (Hoover Institution and Archives, Association of Space Explorers 1983-85, Box 1, Folder 1.) Cliched statements, for sure, but not, I believe, devoid of genuine belief.

The heartland of the Russian nation, as seen through the Gagarin cult, was not in Moscow but in Gagarin’s hometown of Gzhatsk. Renamed “Gagarin” after the cosmonaut’s death in 1968, the town is a typical Russian provincial backwater. In the words of one ode to Gagarin entitled, “The Native Side of Things,” the cosmonaut grew up among vast “expanses of flax and thick meadows of clover,” surrounded by honeybees and butterflies, yet at the center of the country. Rivers and rivulets flowed northward to Leningrad and southward “to the Mother Volga, and then meandered their way to the little father (batiushka) Dnieper.”[1]

As I noted in my first post (“Creating Cover Stories: A National Pastime”), an intense feeling of vulnerability and insecurity had compelled the Soviets, along with Russia’s authoritarian traditions, to surround Yuri Gagarin’s flight in secrecy. But they paid for their secret ways in the coin of rumor — a legacy that survives as the world celebrates the fiftieth anniversary of Gagarin’s flight this April 12. As a noted geographer once remarked: “When we wonder what lies on the other side of the mountain range or ocean, our imagination constructs mythical geographies.” Gagarin’s flight and life were (and will forever be) a mythical geography.[1]

To navigate the mythical realms of Gagarin’s flight I have analyzed special summaries of foreign press reports (located in the State Archive of the Russian Federation). Those summaries, with occasional commentary, were provided by Soviet analysts. Those analysts systematically sampled the foreign press, and also the climate in the Moscow press corps, for reactions to Soviet space exploration. The target audience for these reports was apparently the political leadership as well as managers of the Soviet space program.

When I began my study of Yuri Gagarin many years ago, my biggest challenge, as any historian who has worked in Russian archives can appreciate, was getting access to sources. Gagarin was and remains not just a Soviet icon — but a Russian icon, manipulated and exploited for various patriotic purposes by Soviet and post-Soviet governments. That is especially the case with the fiftieth anniversary of Gagarin’s flight less than two weeks away. Vladimir Putin has personally chaired the organizing committee for celebrations. Relatives, cosmonauts, government officials, museum workers, and curators have arranged the proverbial wagons around Gagarin to protect him from any attempt to tarnish his image — either those based on historical evidence or those concocted from urban myth and hearsay (the main source of information about Gagarin for many journalists, as noted in my previous blog).

A recent controversy surrounding the biography of Yuri Gagarin, and involving NPR, highlights the gaping divide separating academic history writing and the public presentation of history. Last week Robert Krulwich, who writes on science for NPR, posted a blog based on a 1998 book entitled Starman (http://www.npr.org/blogs/krulwich/2011/03/21/134597833/cosmonaut-crashed-into-earth-crying-in-rage). The blog uncritically presented the book’s dubious account of the tragic death of the cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov on April 24, 1967. Gagarin was the back up for that flight. Historians at NASA immediately alerted fellow blogger Asif Siddiqi and me to the blog. Asif, who knows the history of Soviet space better than anyone, posted his critique of the NPR article, followed by many others (see the comments following the blog above). To his credit, the journalist involved has decided to investigate further(http://www.npr.org/blogs/krulwich/2011/03/22/134735091/questions-questions-questions-more-on-a-cosmonauts-mysterious-death?sc=emaf).

Colleagues at cocktail parties and in the lounges of hotels after conferences have often asked me why Yuri Gagarin was chosen to be the first cosmonaut on April 12, 1961. This blog, excerpted from a draft of my book on Gagarin, describes the circumstances that led to Gagarin’s selection as the world’s first spaceman.

Warriors into Spacemen

The decision to send a man into space begged a number of questions, including the type of person required for the job.[1] Sergei Korolev, the Soviet rocket pioneer known publicly as the “Chief Builder” until his death in 1966, had initially argued that the first cosmonaut should be an engineer – perhaps even himself – although he soon backed away from that position. The debate was quickly decided in favor of a fighter pilot, although the space capsule was totally automated and required little “piloting.” The decision had more to do with politics and conceptions of heroism than anything else. It was assumed that fighter pilots had the courage to overcome the potentially terrifying experience of weightlessness and that they would follow commands no matter how dangerous the mission. Besides, if something glorious in the air was to be done – should the cosmonaut survive — then it seemed obvious to most that it should be a fighter pilot, the most heroic of the heroes in the Soviet pantheon after World War II. Finally, drawing the first cosmonaut from military ranks was essential to Korolev’s ongoing campaign to win over the military leaders, who would never have tolerated a mere civilian as the first human being in space.[2]