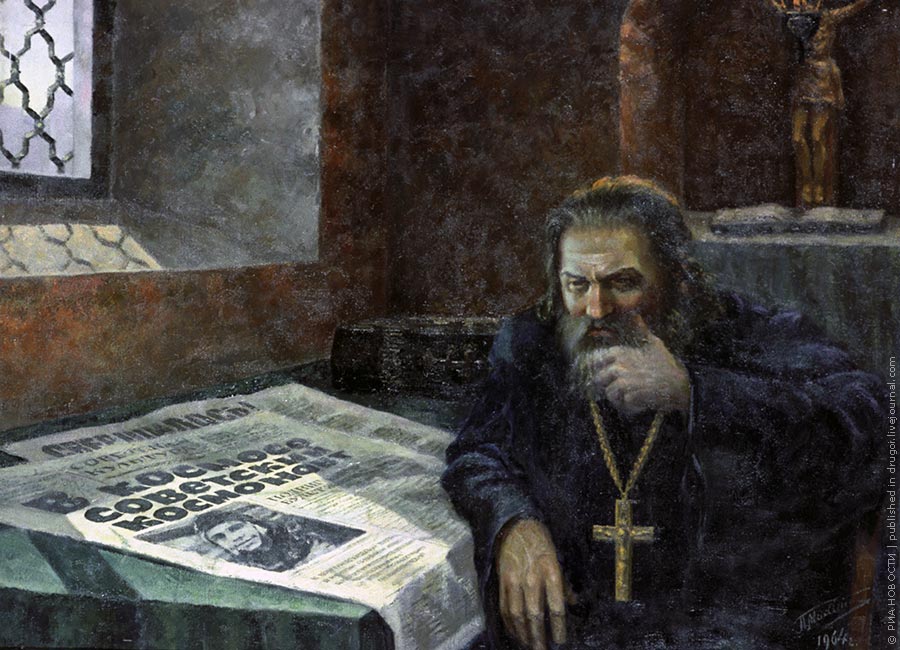

Adding to the previous thread of comments about Gagarin and religion, perhaps the most striking amendment to the Gagarin legend since the collapse of the Soviet Union has been his re-imagination as a devout Russian Orthodox Christian. I often heard from Gagarin’s acquaintances and Gagarin museum officials that Gagarin was secretly a believer.

Adding to the previous thread of comments about Gagarin and religion, perhaps the most striking amendment to the Gagarin legend since the collapse of the Soviet Union has been his re-imagination as a devout Russian Orthodox Christian. I often heard from Gagarin’s acquaintances and Gagarin museum officials that Gagarin was secretly a believer.

New legends also emerged about Gagarin’s efforts to save local churches from being blown up during Soviet anti-religious campaigns. “He did not reject God!” proclaimed a local poet in a poem entitled “Faith.” If Gagarin was a kind of Jesus, his mysterious death in a 1968 plane crash (at the age of 34, just like Jesus) was a test of faith, an act of sacrifice that challenged Russians to consider their sinful nature and united them in grief. Said another poet from his hometown: “He gave his life for us/So that people would remember and value him…Oh, how my dove of peace circles overheard!/Over Gzhatsk he will fly for all eternity.” (Gzhatsk-Gagarin. 300 Let: Stikhi, poemy, pesni [Moscow: Veche, 2007], 83-84.)