This intriguing 2014 documentary takes place in an obscure part of the former Soviet Union called Abkhazia – a tiny sub-tropical mountainous region on the coast of the Black Sea (“Letters to Max,” https://vimeo.com/89560258). This country of 242,000 residents, most of them ethnic Abkhazians who practice Eastern Orthodoxy and who speak Russian, is ostensibly a part of the post-Soviet nation of Georgia. But like many former Soviet territories, simmering ethnic tensions exploded as the Soviet Union disintegrated, turning into a brutal civil war in 1992 and 1993. The Georgian forces were defeated, leading to the expulsion of ethnic Georgians from Abkhazia and a ceasefire in 1994 enforced by a combination of United Nations and Russian peacekeepers. Abkhazia’s independence, however, has only been recognized by Russia, Nicaragua, Venezuela, and Nauru. The forces of Abkhazia periodically clash with the Georgian army as the nation-in-formation, with Russia’s help and in opposition to the United States, seeks international recognition.

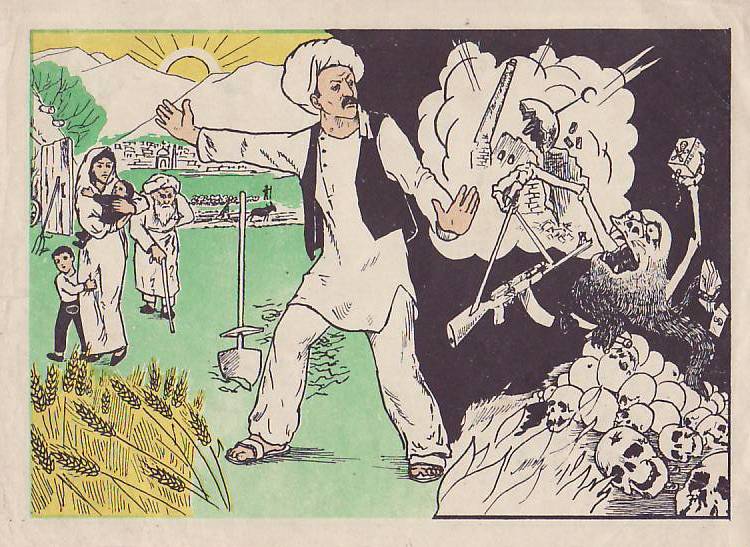

Abkhazia’s fate provides a window into two processes. The longer-term process is the formation of modern nation-states, which invariably involves competing forces who claim to represent the “real nation” and who seek backing for their claims. The second is the backdrop of the Soviet Union’s attempts to build national communities within the confines of its vast borders. It was a project that simultaneously promoted and suppressed a bewildering array of national identities and various levels of cultural and political autonomy for hundreds of ethnic groups. The tensions and conflicts created by Soviet policies were contained only by Soviet authoritarianism and by the communist party of the Soviet Union. When both the party and the Soviet Union collapsed, unresolved national tensions, exacerbated by various land grabs by newly independent and former Soviet national republics, produced a number of frozen conflicts along the Russian Federation’s borders – in Moldova, Ukraine, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, just to name a few.

The documentary tells the story of Abkhazia’s search for legitimacy through a diplomat named Maxim Gvinjia, whose mission since the Soviet Union’s collapse has been to establish Abkhazia’s place in the community of recognized nation-states. During the course of filming “Max” occupied various positions inside and outside Abkhazia’s Foreign Ministry, eventually becoming Foreign Minister in 2013 for a brief period. The filmmaker (“Eric”) uses the narrative device of the letter to tell his story, filming Max as he opens letters from “Eric” in Paris in which Eric asks Max a question regarding his job and life. The film consists of Max’s responses to those questions, set against the backdrop of Abkhazia and Max’s daily routines.

Max is an amiable and interesting narrator, with the detached and wry sense of humor of a person (and people) whose experiences defy clichéd conceptions of liberation, democracy, national sovereignty, and progress. The film opens with Max wondering about Eric’s question of where exactly he is. His philosophical answer touches on one of the central dilemmas of the modern nation-state, namely, that most people’s identities and sense of self do not match the ideas about identity projected by the state that purports to embody their “will.” Max points out that there are many recognized countries, such as Somalia, Afghanistan or Yemen, which make little sense as nation-states. The way various peoples within those states self-identify rarely match state conceptions and often are violently at odds with official political visions. Max claims that Abkhazia, in contrast, is unique in the relative perception by its citizens and state leaders of a united community of interests and identity.

Abkhazia is a beautiful country, situated in a mountainous region that hugs the Black Sea Coast. The spectacular coastline views combine with a human-built world which, like much of the former Soviet Union, is in a state of exquisite decay and dilapidation – a place frozen in a Soviet past, similar to the frozen political conflicts that provide the political and social equivalent of a landscape. For Max, the state of decay is a starting point for his own discourse on nostalgia for the Soviet period, when the Abkhazian sea city of Sukhum (known in Soviet times by the Georgian Sukhumi) was a meeting point of cultures and peoples, and also a resort town for Soviet citizens. With its harbor, Sukhum in the Soviet era was far more open to the world and various peoples than other parts of the Soviet Union. That openness contrasts with the city’s current isolation in the post-Soviet world – yet another one of the many ironies highlighted by Max in his letters and discourses on camera.

The director is careful to ask tough questions of Max, especially regarding the fate of Georgian refugees, who are unable to return to the Abkhazia that their families for centuries called home before the war of 1992-1993. Does creating a new Abkhazia mean erasing their memory? Is the coherence of Abkhazia as a nation-state, in which the identity of its citizens seems to match ideas about identity projected by the state, a result of ethnic cleansing? Max’s very surprisingly honest and apolitical answer — perhaps one reason for his being sacked as Abkhazia’s foreign minister — is both yes but also that the fate of Georgians is part of the tragedy and irreversible change in Abkhazia as a result of the Civil War. There can be no return to the Soviet period, though Max admits he would love to do so, when ethnic harmony was supposedly far more the norm than the exception. With regard to a question regarding whether Abkhazia has escaped from Georgia only to be eaten up by Russia and become a playground for Russian Oligarchs, Max is unequivocal. Russians, says Max, are the ones willing to buy Abkhazian products, spend tourist dollars in Abkhazia, and support Abkhazian independence. Given the limited range of options for Akbhazians, and the reality of Russia’s presence, Abkhazia has no choice but to align itself closely with Putin and the Russian Federation. The Mexicans say, “It’s the same hell only with a different devil.” For the Abkhazians, aligning with Russia is not quite the same hell, and perhaps preferable to Georgia, but few Abkhazians would mistake Russian leaders and oligarchs for saviors.

Nemeth claims he joined the communist party in the early 1960s to try and change it from within. His father did not speak to him for six months but eventually reconciled himself to his son’s decision, telling him only that he must tell the truth to his people and to the world if he were to attain a position of power. He took that advice when he traveled to Moscow to meet Gorbachev, nervous but determined to discuss his reform plans, including holding free elections that would almost certainly result in the victory of non-communists and to remove the fence that the Hungarian treasury could no longer maintain. To his great surprise, Gorbachev greeted him with a firm handshake rather than the sloppy kiss and warm embrace typical of Brezhnev’s encounters with Eastern European counterparts.

Nemeth claims he joined the communist party in the early 1960s to try and change it from within. His father did not speak to him for six months but eventually reconciled himself to his son’s decision, telling him only that he must tell the truth to his people and to the world if he were to attain a position of power. He took that advice when he traveled to Moscow to meet Gorbachev, nervous but determined to discuss his reform plans, including holding free elections that would almost certainly result in the victory of non-communists and to remove the fence that the Hungarian treasury could no longer maintain. To his great surprise, Gorbachev greeted him with a firm handshake rather than the sloppy kiss and warm embrace typical of Brezhnev’s encounters with Eastern European counterparts.

The exodus, involving many of East Germany’s most highly qualified professionals, who believed they had good prospects in West Germany, enraged the East German leader Honecker, as well as the remaining hard liners still in power in Bucharest, Prague, and Sofia. As in 1960, when there was a mass exodus of East Germans to West Germany in Berlin, the East German government demanded that the Soviet Union plug the hole in the Iron Curtain that was allowing the best and brightest in East Germany to leave. But unlike Khrushchev, who responded by building the Berlin Wall, Gorbachev refused to stop the mass emigration, consistent with his promise to Nemeth earlier that he would not interfere in plans to remove the electric fence between Hungary and Austria whose absence now provided an exit path for East Germans. That refusal set into motion the dramatic events that led first to Honecker’s ouster in October 1989, the collapse of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and the disintegration of communist control in Eastern Europe shortly thereafter.

The exodus, involving many of East Germany’s most highly qualified professionals, who believed they had good prospects in West Germany, enraged the East German leader Honecker, as well as the remaining hard liners still in power in Bucharest, Prague, and Sofia. As in 1960, when there was a mass exodus of East Germans to West Germany in Berlin, the East German government demanded that the Soviet Union plug the hole in the Iron Curtain that was allowing the best and brightest in East Germany to leave. But unlike Khrushchev, who responded by building the Berlin Wall, Gorbachev refused to stop the mass emigration, consistent with his promise to Nemeth earlier that he would not interfere in plans to remove the electric fence between Hungary and Austria whose absence now provided an exit path for East Germans. That refusal set into motion the dramatic events that led first to Honecker’s ouster in October 1989, the collapse of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and the disintegration of communist control in Eastern Europe shortly thereafter.